The smell hit her first. Thick, sweet, unmistakably foreign. Smoke curled through the air, carrying hints of grilled meat, spiced sauce, and something warm that wrapped itself around her like memory. Standing in a dusty Texas field behind the camp’s wire fence, the young Japanese nurse could hardly believe what she was seeing.

A row of American cowboys, hats tilted against the sun, gathered around a massive iron grill. One of them, tall, sunburned, apron tied over his boots, waved her forward. She didn’t move. This had to be a trick. She had been told captivity meant shame, hard labor, cold stairs. But this this was an invitation.

Others hesitated beside her, uniforms hanging loose on thin frames, their eyes darting between the guards and the picnic tables. Then slowly the gate creaked open, not with commands, with welcome. “Ladies,” one cowboy said gently. “It’s barbecue night.” The world tilted. She stepped forward, heart pounding, and just like that, everything they believed about the enemy began to unravel.

The unraveling had not begun with barbecue smoke. It had started weeks earlier beneath the groan of a ship’s engine cutting through the Pacific. The young nurse, barely 22, had stood pressed against the steel wall of the hold, crammed among rows of other women with shaved heads and threadbear uniforms. They had been captured outside Okinawa, pulled from field hospitals and logistics posts, rounded up like weward ghosts. The ship had smelled of diesel, seawater, and vomit.

No one spoke above a whisper. Fear was an unspoken language etched into every hunched shoulder and clenched jaw. Each woman carried with her the weight of an oath, that surrender was shame, and captivity worse than death. Yet here they were, alive, disarmed, unmed. The ocean stretched in all directions, offering no answers.

Occasionally a guard above would shout instructions in English, the words sharp and strange, impossible to decipher. And below the women waited, not for rescue, but for whatever came next. It was America that came next, not as myth or caricature, but as something physical and impossible to reconcile.

The train they were herded onto hissed and lurched, dragging them inland from the harbor. At every stop they expected to be unloaded into labor camps or public squares for humiliation. But the journey continued endless. The land outside changed slowly from city outskirts to open fields, the horizon flattening out into something vast and eerily clean.

They passed windmills, cows grazing on bright green pastures, small white churches, and boys riding bicycles alongside dirt roads. The nurse kept waiting for the ruins, for the smoke, for something recognizable in the shape of war. But it never came. America did not look like a victor. It looked untouched, uninterested.

The sun was too warm, the sky too wide, the silence too complete. It was disorienting, as if they had stepped into a stage play where the war was already over, and no one had informed them they were still losing. When the train finally groaned to a halt, the women did not know where they were. The sign outside the station read Camp Wayright. But the letters meant nothing.

The guards called orders in English and pointed toward waiting buses. The women obeyed. They always obeyed now. The nurse sat beside a woman who clutched a photo in her lap. A baby boy wrapped in cloth born before the firestorms. She whispered a prayer beneath her breath. The entire ride, no one stopped her.

The camp appeared suddenly, not like a prison, but a fenced village tucked into the Texas landscape. Guard towers punctuated the corners, but no dogs barked, and no weapons were raised. The buses rolled to a stop. A young American soldier stood waiting with a clipboard and a pencil behind one ear. He looked no older than her younger cousin, who had died in the Philippines.

He didn’t smile, but he didn’t scowl either. Processing began with mechanical precision. The women were led into a low building with peeling paint and humming ceiling fans. Inside their names were recorded, or approximations of them, and small canvas bags were handed out containing a towel, a plain dress, and what looked like soap.

Their uniforms were stripped from them one by one. The nurse trembled as she unbuttoned her blouse, waiting for the shout, the sneer, the slap, but none came. A female officer, American, offered her a plain cotton shift and gestured toward a line of showers.

There were no learing guards, no laughter, just water hissing behind tiled walls and the scent of something faintly floral. The nurse stepped under the spray and wept quietly, the dirt of weeks washing down the drain like something sacred. After the showers, they were led to a barracks, long wooden buildings lined with bunks and wool blankets folded tightly at the foot of each bed.

It reminded some of them of school, others of hospitals. The nurse thought only of how the blanket smelled faintly of starch, and how it was the first thing she had touched in months that wasn’t damp, rotting, or bloodstained. That night, as the sun sank beyond the wire, they lay in silence. No guards shouted, no footsteps echoed.

Only the chirp of crickets and the hum of electric lights outside. And that silence, that terrifying, disarming silence became the first true shock of captivity. They had been prepared for cruelty. What they found instead was order, cleanliness, and something far more dangerous, the suggestion of normaly. As the nurse stared at the knot in the wood above her bed, she whispered to herself what none of them dared say aloud.

What if we are not here to be punished? What if we are simply here? The thought alone was enough to make her heart race, because if captivity did not mean brutality, then what else had they been wrong about? It started with breakfast. The nurse was woken by the clang of a distant bell and the low murmur of footsteps outside the barracks.

She sat up slowly, unsure if she had dreamt the silence of the night before. around her. The other women stirred beneath wool blankets, blinking into the dim light that filtered through wooden slats. No shouted orders, no barking dogs, just the smell. At first it was indistinct, then unmistakable coffee. Real coffee. Not barley substitute or burnt rice husks, but something richer, darker, foreign.

It wafted through the cracks like an invitation. She followed the others outside, shivering slightly in her plain dress. The mess hall loomed ahead, larger than it had any right to be, and from inside came not the clatter of chains, but the dull rhythm of trays sliding along a metal counter. They entered hesitantly. The guards stood back, arms crossed, watching, but not interfering.

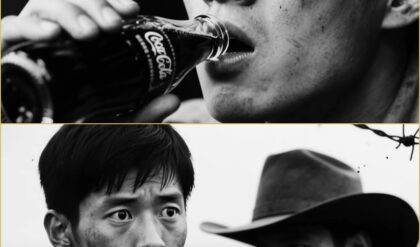

One woman froze in the doorway, clutching her stomach as if the smell alone might wound her. The nurse stepped forward, pushed by the motion of the line, and took a tray with trembling hands. A soldier behind the counter, not much older than she, ladled something thick and steaming into her bowl. beef stew, potatoes, a soft white roll that gleamed as if brushed with butter, a mug of the coffee, dark as ink. She moved along in silence, stunned.

This couldn’t be real. In the last months of the war, she had survived on rice stretched with sawdust and watery broth that smelled of rot. She had seen comrades faint from hunger, and others carve bits of leather from their boots just to chew. Yet here, in the enemy’s hands, she held a tray heavier than any she’d touched in years.

Sitting down, she stared at the food. The others did, too. No one moved. One woman whispered that it might be a trick, that poison would be slower this way. Another crossed herself and took a bite, chewing with her eyes closed. The nurse lifted her spoon. The stew was rich, the meat almost sweet with fat, the broth clinging to her lips in a way that made her chest tighten.

She swallowed, and her body jolted as if waking from something ancient. Across the table, another prisoner, a girl who had once worked in a supply depot in Nagasaki, bit into the bread and began to cry. It was too much. Not the food, the idea of it, the abundance, the kindness implied in warm meals and buttered rolls. It fractured something inside them.

Later that day, they were handed small packets. Inside, peanut butter. Most had never seen it before. One woman dipped her finger in, sniffed it, then gagged at the taste. Another, braver, took a bite, and burst out laughing, the sticky sweetness coating her teeth. Her laughter echoed strangely in the room. No one punished her.

A guard glanced over, but didn’t react. It was the first sound of joy any of them had made since capture, and it terrified them. How could something as absurd as laughter survive here? Confusion followed. Gratitude tangled with guilt. Every bite of food reminded them of the children scavenging in the streets of Hiroshima, the mothers in Osaka boiling weeds for soup.

The more their bodies filled out, the more their thoughts withered under shame. At night they whispered about it. Could they be fed by their enemies and still remain loyal to their homeland? Could nourishment be both mercy and weapon? But hunger doesn’t ask for permission. Over the next days, suspicion didn’t vanish, but it softened. The nurse found herself looking forward to breakfast, to the scent of something fried, to the brief escape from the hollowess she had carried for so long.

And with each meal, something unexpected took root. A flicker, a whisper, not hope, not yet. But the fragile, flickering idea that survival and dignity might not be enemies after all. Then came the smoke. It drifted over the fence one afternoon like a scent from a different world, sharp, sweet, rich with fat and woodfire.

The prisoners gathered instinctively near the wire, sniffing the air like animals unsure whether the smell meant danger or safety. It was meat, grilled meat, not boiled, not hidden in stew, but open flame, seared, and unapologetic. Someone said the Americans were celebrating something. A few others guessed it was bait. The nurse stood among them, hands clenched at her sides, watching as cowboy hats bobbed in the distance. The smell was maddening.

It called forth memories of family picnics before rationing, before bombings, before the sea swallowed half the coast. She did not know what to feel. She only knew that her stomach achd. and something older, pride, fear, maybe both, pushed against the edges of her ribs. The invitation came not with fanfare, but a short announcement relayed through a translator.

The prisoners were welcome, not required, to attend a cookout with local ranchers and camp staff. A gesture of goodwill, they said. No speeches, no ceremonies, just food. Some of the women froze, their bodies stiff with suspicion. One older woman, who had served in a field hospital near Saipan, turned away immediately. We are not dogs to be fed for show, she hissed, but most didn’t move.

Not yet, not forward, not back. The idea itself was incomprehensible. to be invited to eat with the enemy, to be offered not just a meal, but a place. The nurse didn’t sleep that night. She lay awake, staring at the ceiling beam above her cot, tracing the knots in the wood like stars in a sky she no longer trusted.

By morning, the smell of smoke had returned, stronger now. Something had changed in her, not broken, softened. She joined the others who were lined up at the gate, unsure what they were walking into. The guards opened it without ceremony. No rifles raised, no barking commands, just a quiet gesture to follow.

The cookout was held just outside the wire beneath a wide tree that offered little shade but plenty of breeze. Long tables had been set up, covered in red and white cloths. Plates waited beside piles of grilled beef, roasted corn, white buns, and a thick red sauce some of the women had never seen before. One sniffed it and recoiled. Ketchup. Another wept at the site.

My son, she said through tears, always asked for red sauce. She hadn’t seen him since the Manurion evacuation. The guards did not stand apart. They sat too alongside the prisoners, eating from the same plates, drinking the same sweet tea. The cowboy who served the food didn’t shout, didn’t lear.

He only smiled, plate in hand, and said, “Hope you’re hungry, ladies.” It was the first time any of them had been addressed that way in years. Not as auxiliaries, not as enemies, just women. As the nurse sat and took her first bite of grilled meat, hot, charred, soaked in spice, she found herself swallowing not just food, but confusion. The taste was exquisite, almost violent in its richness.

It forced her to confront something she wasn’t ready to name. What do you do when kindness tastes better than victory ever promised? What about you? Where are you watching this from right now? Let us know in the comments below. It’s like sending a letter through time. These stories, like the smoke curling off the fire that day, float across decades looking for listeners.

And if you’re finding this one as unbelievable and powerful as these women did, don’t forget to gently press the like button and subscribe by tapping the button just below this video. then hit the little notification bell. It’s what keeps stories like this one alive. Stories where war didn’t just destroy lives.

It revealed humanity in the most unexpected places. By the end of the meal, the tables were smeared with sauce, the sun dipping lower into the Texas sky. Some of the women were laughing, not all, not yet, but a few. and not the hysterical kind born from fear or hunger, but something lighter, warmer.

The nurse caught herself smiling at the cowboy, who refilled her tea, and quickly looked away. It didn’t make sense. But then again, neither did surviving. She glanced at her hands, still holding the plate, and realized they were no longer shaking. That night, she lay in bed and didn’t cry. She didn’t even pray.

She simply stared at the ceiling and whispered aloud, “They fed us like neighbors.” And in that single sentence, the war, or at least the war inside her, shifted, not ended, not one, but changed, and it had all begun with smoke. The fire had died down by then, its embers glowing beneath the blackened grill.

The nurse sat quietly at the edge of the table, her plate scraped clean, her fingers sticky with sauce. Around her, the other women lingered in the aftermath, some wiping their mouths with cloth napkins, others still clutching untouched buns as if they might disappear. And then something strange happened. One of the guards stood up to stretch, and as he reached for a jug of sweet tea, his sleeve rolled back just enough to reveal a thin gold band around his finger. A wedding ring.

It glinted briefly in the fading light, but that small detail caught the nurse like a nail to the heart. She had spent years picturing American soldiers as beasts, faceless conquerors who saw Japanese women as little more than war trophies. But here was a man with someone waiting at home. A wife, maybe children, someone who had promised to return. She couldn’t stop looking at his hand.

Nearby, two other guards argued in mock serious tones over whose barbecue sauce was better, Texas style or Carolina style, their words punctuated by exaggerated gestures and laughter. One of the prisoners chuckled softly at their debate. Another shook her head in disbelief. The scene didn’t make sense. War didn’t look like this.

War wasn’t supposed to have jokes or wedding bands or ketchup bottles lined neatly on tables like condiments in a summer picnic. It was supposed to be smoke and screams and shattered glass. But here, under the vast American sky, war looked like a summer afternoon, and that somehow was more disorienting than any prison cell could have been. The nurse tore her gaze away and looked down at her hands. They were stained with grease. Her knuckles sunburned.

Her stomach was full, something she hadn’t felt in months. And yet she felt hollow in a way that had nothing to do with hunger. The contradiction was unbearable. How could the same country that firebombed Tokyo give her a second helping of cornbread? How could the same uniforms that haunted her sleep also belonged to boys who passed around guitar cords and poured sweet tea into paper cups? The indoctrination they carried, folded into every corner of their training, began to peel like old wallpaper. They had been told to bite

their tongues until blood flowed before speaking to an American. They had been told kindness was a trick, a disguise for domination. They had been warned that surrender meant losing not only their freedom, but their soul. But here they sat and chewed and swallowed and laughed. It didn’t fit. The foundations were cracking, and no one knew what would be left standing when the walls came down.

That night, guilt crept into the barracks like fog. One woman lay awake, whispering apologies into her pillow, her voice thick with shame. Another turned her face to the wall and refused to speak until morning. The nurse sat up in bed, replaying every bite, every glance, every small moment when the line between captor and companion had blurred. It wasn’t just the food.

It was the warmth of it, the absurdity of paper napkins, the strange comfort of guitar strings plucked without tension. These were not acts of strategy. They were human gestures, and that more than anything frightened her, because if they weren’t monsters, if the Americans were capable of compassion, what did that say about the officers who taught them otherwise? What did it say about the silence of her commanding nurse, who had allowed wounded men to die in agony rather than risk capture? What did it say about the voices that had shaped her? The books that taught her to revere the empire, the whispered prayers that warned her

against softness. She closed her eyes and saw the cowboy again offering her a plate without ceremony. No orders, no threats, just dinner. And in the smoke drifting off the grill, she realized that the real battle had only just begun. It wasn’t a war of bullets anymore.

It was a war of memory, a war of belief, and she didn’t know who was winning. The announcement came on a morning like any other, the sun already burning high, the dust settling over the gravel paths that cut through the camp like scars. A translator, flanked by two American guards, stepped into the barracks and spoke softly but clearly. The women would be allowed to write letters home. At first, no one reacted.

Not out of calm, but paralysis. It was too strange, too much. The idea of correspondence, of ink and paper crossing oceans and battle lines felt absurd. Some thought it was a trick. Others whispered warnings from their training. Never confess, never document, never speak.

But then the guards handed out the supplies, real paper, sharpened pencils, envelopes. The women took them with hesitant hands as if touching something forbidden. The nurse sat at the edge of her bunk and stared at the blank sheet in her lap. What was there to say? What was there she dared to say? She hadn’t seen her mother in over two years. Her last letter from home had been a fragment. A prayer scrolled between ration coupons.

Was her brother still alive? Was the house still standing? Could her words reach them? And if they did, what would they carry around her? Others struggled with the same questions. Some wept before writing a single word. Some folded the page untouched, returning it as if to deny the reality of their own survival.

But slowly the graphite began to scratch. One woman wrote simply, “We are not in chains. We eat rice and meat.” Another wrote of the blankets, “How they smelled faintly of soap and warmth.” One described the cookout in hushed, fragmented sentences. “They grilled meat. There were sauces in small glass bottles. The Americans sat with us. They laughed. Each sentence felt like an act of disobedience.

not against the Americans, but against everything they had been raised to believe. The nurse wrote carefully, her handwriting narrow and neat, as if shrinking the words would shield her from consequence. I ate meat. I was not punished. I don’t know what to think. No one was certain the letters would be sent.

They knew they would be read first, censored, copied, passed through layers of military intelligence, but that didn’t stop them. In a strange way, it made the writing easier. They weren’t just speaking to their families. They were speaking to the system that had delivered them here. To the men in Tokyo who still preached death before capture. to the officers who had warned them the Americans would tear out their teeth and laugh as they starved.

Each word was a blade against those lies. Still, much was left unsaid. No one wrote of the guilt, of the shame that crept in with every warm meal, of the strange, terrifying ease with which the days passed. No one described the way they looked forward to the smell of breakfast, or how they no longer flinched at the sight of a guard’s shadow. Some truths couldn’t be written. Not yet. Maybe not ever.

Weeks later, rumors drifted back from the Red Cross. The letters had reached Japan, or at least copies of them had. They had been intercepted, reviewed by military officials, quietly cataloged, and they had caused alarm. The narratives unraveling inside the camp were now beginning to unravel outside it, too. The idea that women, daughters of the empire, were being treated with decency, with humanity, was more dangerous than any bomb.

Back home, families read between the lines. A mother in Kyoto clutched her daughter’s letter and whispered, “She’s alive.” A husband in Saporro wept over a sentence that mentioned clean sheets. A former officer, still loyal to the regime, read a prisoner’s account of barbecued meat and slammed his fist against the table. “Lies,” he muttered. But he read it again.

In the camp, the nurse folded her letter and sealed it with a trembling hand. She didn’t know if it would arrive. She didn’t know what it would do. But as she passed it to the guard at the gate, she realized something quiet and irreversible had happened. She had told the truth. Not the whole truth, but enough. And once told, it could not be untold.

The paper was thin, the pencil faint, the language restrained, but the words were like seeds. And somewhere across the ocean, they had already begun to take root. The next morning, the camp smelled like bacon again. The nurse lay in bed, eyes wide open, the scent curling through the thin wooden walls like a memory she didn’t own. It was greasy, warm, unrelenting.

The smell of frying fat and black coffee rising with the sun. She hated how familiar it had become, hated how her mouth watered. Outside, boots crunched against gravel, and laughter drifted between the barracks like smoke. The Americans were awake, whistling, joking. Someone was already playing the guitar.

It was always like this now. The camp, once terrifying in its silence, had taken on a strange rhythm. Days that began with breakfast lines and ended with twilight songs from the far end of the compound. One guard, the young one with the worn out boots and a face like a school boy, had a guitar he played every night. Country songs mostly.

Foreign rhythms strumed lazily under the Texas sky as the prisoners lay in their bunks listening, some in anger, others in disbelief, a few in something dangerously close to comfort. Sometimes the nurse caught herself tapping her fingers to the beat. Once she hummed just under her breath, and stopped immediately, cheeks burning.

It was easy to forget for a moment who they were, easier still to forget what was waiting beyond the fence. The barbed wire was still there. The guards still held rifles. And yet there was something softer now. One evening, as the guitar hummed and dusk rolled over the fields, a guard attempted to say good night in Japanese, he butchered the word completely.

One of the women, the youngest among them, laughed, not mockingly, but as if the sound itself surprised her. The guard grinned and tried again. This time he got closer, and she replied softly, “Good night.” These moments chipped away at the walls more effectively than any sermon or gesture of diplomacy. They were not political. They were not scripted.

They were accidental truths, glimpses of the world beneath the uniform. The nurse watched it happen. A shared look over a tea kettle. A guard who picked up a dropped photograph and handed it back without a word. A prisoner who asked cautiously how to say thank you in English, and who then used it. One afternoon she heard the whistling again, offkey and persistent.

She stepped outside to see the same young guard standing awkwardly with one of the women, gesturing with his fingers as if shaping sound in the air. He was teaching her to whistle. She was trying, failing, laughing quietly at herself. Not a performance, not a trap, just two people making noise.

The nurse stood in the doorway for a long time, something tight and strange pressing behind her ribs. When the woman finally managed a single clean note, the guard applauded like it was a stage act. And for a moment they both looked like children, it was unbearable. Because what does it mean when the enemy becomes less frightening than your own memories? When your body responds to kindness before your mind can remind it not to. The laughter in the camp wasn’t loud.

It wasn’t constant, but it was there. It came in snorts over bad English, in suppressed giggles when someone mispronounced hamburger, in the soft tremble of shoulders during evening roll call, when someone dropped a tray and no one yelled. The laughter wasn’t surrender. It was something more radical.

It was rebellion not against the Americans, but against the fear that had defined them for so long. A refusal to let war dictate every breath, every blink, every scrap of identity. And yet, even as laughter crept in, it brought with it the ache of guilt. Each smile felt like a betrayal.

Each moment of peace, a weight pressing harder than punishment ever had. Still, the nurse couldn’t deny it. The camp no longer felt like a cage. It felt like a contradiction, one she couldn’t yet name, but one that smelled most days like bacon, and sounded most nights like guitar strings under stars she had never bothered to look at until now. The music did not stop with summer.

It carried into autumn, threading its way between the barracks like a tune that refused to fade. The days blurred into a rhythm so gentle it became its own kind of torment. For the first time in years the women were not starving, not freezing, not hunted. And that somehow was harder to endure than hunger or fear had ever been. The nurse could feel it in her bones, a new kind of exhaustion, one born not of pain, but of safety.

It was a dissonance she couldn’t name. The Americans treated them with a politeness that should have been comforting. Instead, it felt like standing in sunlight after living too long underground. Everything too bright, too soft, too exposed. At first, the women thought the feeling would pass. It didn’t.

The more they were treated as people, the heavier their hearts became. They began to remember the words drilled into them during training, that surrender was shame, that captivity was worse than death. Now those words clashed with the evidence of their own bodies, fed and clothed and healing under the care of their enemies. The contradiction pressed on them like a bruise that would not fade.

One woman, a former typist from Osaka, stopped eating for 3 days, not out of protest, but confusion. “It feels wrong,” she whispered. “To be full while my mother starves.” The nurse tried to reason with her, but she had no language for the paradox either. She herself had woken one morning to find her skin clearing, her cheeks filling out.

She looked in the mirror. A piece of polished metal hung above the sink and barely recognized her own reflection. The woman staring back looked alive. It frightened her. Then came the parcels. Red cross deliveries, the guards explained. Humanitarian aid. Each woman received a small box with her name written on a card.

Inside a toothbrush, a bar of chocolate, soap, toothpaste. The nurse lifted the items one by one as though they were relics from another world. The toothpaste tube shimmerred in the light, blue and silver, marked with English words she couldn’t read. Someone whispered that it might be poison.

Another laughed a brittle, fragile sound, and said, “Then at least it will taste clean.” But when the nurse squeezed a line of paste onto her brush and brought it to her mouth, the mint burned cold against her tongue. It wasn’t poison. It was purity, foreign, shocking, intimate. She brushed until her gums bled. Then she sat on her bunk and cried quietly into her hands.

That night the camp was unusually silent. No guitars, no laughter. The weight of kindness had settled over them like fog. It wasn’t gratitude that filled their chests, but grief. Because to accept the Americans gentleness was to acknowledge that their own leaders had lied. that all the pain, all the sacrifice, all the death had been for nothing but pride.

The empire had demanded loyalty unto death. Yet here they were, living proof that mercy had saved them instead. Some of the women began praying again, not for victory, but for forgiveness. Others retreated inward, their silence thick as walls. The nurse listened at night to the sound of breathing in the barracks. Dozens of women caught between relief and shame.

One sobbed in her sleep. Another whispered apologies to her dead husband. The next morning, the nurse found the woman who had refused to eat sitting on the steps outside the barracks. Her face was stre with tears, her hands clutching the empty Red Cross box. “They gave me chocolate,” she said in a hollow voice. “It was sweet.

I couldn’t finish it.” Then she laughed, the kind of laugh that breaks before it forms. The nurse said nothing. There was nothing to say. Around them, the camp hummed with quiet industry, guards moving, voices calling, the smell of breakfast drifting through the air. Life went on, indifferent to their unraveling.

And as the nurse watched the sunlight catch on the toothpaste foil lying in the dust, she understood that survival was no longer the hard part. The hard part was living with what survival revealed. By the time the third cookout rolled around, the smoke no longer startled them. It arrived like a familiar wind, curling into the barracks before breakfast, wrapping itself around the flag pole, threading through the cracks in the wood like a memory returning for its monthly visit.

The barbecue was no longer an event. It had become something stranger, a rhythm, a ritual, like the roll call or the ringing bell at dawn. It marked time, not by authority, but by smell and flame. and the faint promise of something warm. In the beginning, most of the women stood stiffly at the edges of the cookouts, arms folded, eyes guarded.

Some refused to eat, some only took bread. One woman had tossed her plate into the dirt the first time, unable to reconcile kindness with captivity. But the fire had kept burning. The meals came again and again and again, and slowly the resistance softened, not broken by force, but worn down by the unbearable weight of repetition.

You can only look at grilled meat so many times before hunger swallows principle. The nurse noticed it in small ways. A woman who had once turned her back now took a seat. Another who had muttered curses under her breath now asked for more beans. Even the jokes started to change. The ketchup, once viewed with suspicion, was now passed down the line like contraband.

One woman laughed when a cowboy called it red gold. She didn’t mean to. It just slipped out. No one scolded her. Then came the afternoon when something unexpected happened. One of the women, her name was Natsuko, a school teacher from Nagano, stepped out of line and walked toward the grill. Her hands were empty, her face unreadable.

The guards tensed for a moment, unsure what she intended, but she didn’t protest. She didn’t yell. She simply reached for a pair of tongs. A cowboy midflip looked at her, eyebrows raised. “You want to help?” he asked slowly, as if testing the weight of the words. She nodded. No one moved.

The camp seemed to pause, the air thick with the smell of charred meat and disbelief. Then, quietly, the cowboy stepped aside. Natsuko rolled up the sleeves of her prison dress, revealing thin arms browned by the Texas sun. She took the tongs. Her hands trembled, not from fear, but from something deeper. Reverence maybe, or disbelief. She turned the meat.

The sizzle was louder than the murmurss that followed. The moment passed without ceremony, no speech, no applause, just one woman flipping food beside a man she had been told was her enemy. But for the nurse, watching from the shade of the barracks, it felt like something cracked open.

not shattered, just opened a door, perhaps a breath. After that, more women stepped forward. Some helped slice onions, others folded napkins. One made a joke about learning American recipes. The gods laughed. One offered a recipe in return. It was all so normal, it became surreal because what they were doing wasn’t surrender. It was participation.

voluntary, unearned, undemanded, and it changed them. Not all at once, and not in the ways they expected, but something shifted. The nurse felt it most in her stomach, how it no longer tightened at the smell of bacon, how hunger no longer felt like shame. Eating had once been an act of defiance, then survival.

Now it was something else entirely, connection. She watched as prisoners and guards stood in the same line, dipped food from the same trays, shared space without tension. It didn’t erase the past. It didn’t undo the war, but it created a moment suspended outside of it.

She still didn’t trust it, not fully, but she could no longer deny its effect. Kindness had not come with flags or speeches. It had come on a paper plate, warm and spiced, handed over a grill with a nod. Change, she realized, didn’t have to begin in the heart. Sometimes it started in the stomach, and the fire kept burning, not out of obligation, but out of something harder to name.

Continuity, witness, hope. It crackled beneath the stars month after month, marking time, not by loss, but by the slow, strange work of nourishment. Then one morning, the fire didn’t light. No bacon, no smoke, no guitar. The messaul was quiet, the guards subdued.

A notice had been posted the night before, translated in careful handwriting, and pinned to the board with a single nail. Repatriation orders confirmed. transport to begin within the week. The women gathered beneath it like they were staring at the face of a ghost. Some wept, others stared blankly. A few, like the nurse, said nothing at all. The war had ended, months ago, in fact.

But now, finally, it had reached them. In the days that followed, the camp changed in texture, not in rules or routine, but in feeling. The women moved through the grounds as if walking in a dream, trying to memorize every sound, every tree, every corner of sky that had held them in place.

While the world beyond burned itself quiet, their steps grew slower, their glances longer. The enemy had become the furniture of their survival, familiar, steady, and now leaving. The nurse folded her belongings into a red crossued bag, two plain dresses, a hand towel, her notebook of unscent letters, and a comb missing three teeth.

She tucked in the bar of soap she’d saved from her first week. Then, after a long pause, she added the smallest thing she had, a near empty glass bottle of barbecue sauce. She had traded for it with another prisoner who couldn’t stand the taste. She didn’t know why it mattered, only that it did, that it had come from this world, not the one she was returning to.

The goodbyes were quieter than expected. There were no grand speeches, no salutes, just nods, handshakes, and one awkward hug from a guard who didn’t seem to know where to place his arms. One woman burst into tears when a cowboy pressed a harmonica into her hand and said, “For the quiet nights.

” Another slipped a folded thank you note into the hand of the camp cook. The nurse simply looked her guitar playing guard in the eye and said, “I don’t know how to say goodbye in English.” He smiled and said, “That’ll do.” But it wasn’t just parting with the Americans that unsettled them. It was the journey ahead.

The train rides would be long, the docks crowded, the ships uncertain, but it was the destination that made their stomachs twist. Home or what was left of it. Cities reduced to ash, families scattered, a nation humiliated, and above all the question of how they would be seen. They had survived. That in itself was a kind of betrayal of those who died, of those who fought, of the ideals they were taught to protect.

What would their neighbors think? What would their mothers say? How do you explain being treated with kindness by the very people you were trained to hate? There was no map for that kind of return. They held their objects tightly as if they might explain what words could not. A letter never mailed. A ragged piece of chocolate foil.

A drawing made by a guard on the back of a meal slip. These were more than souvenirs. They were proof. Proof that the world was not as simple as they had been told. That kindness could wear the uniform of an enemy. that barbed wire could surround a place where healing happened.

The nurse clutched the bottle of sauce in her lap as the truck rumbled toward the coast. The sun burned low across the Texas horizon, turning the dirt roads gold. She closed her eyes and tried to picture the streets of Yokohama, the smell of her mother’s kitchen, the sound of bamboo mats creaking beneath her childhood footsteps. But those memories were dim now.

faded beneath the brightness of new ones of smoke and laughter and guitars at dusk. She didn’t know what waited on the other side of the ocean, only that she would arrive carrying stories no one had asked for, wrapped in objects no one would understand.

And in that silence between her old world and the new, she would be left to translate what couldn’t be said. Not in Japanese, not in English, but in the quiet space where truth and survival meet. The nurse was no longer young. The lines on her face had softened but deepened, as if time had carved its way in slowly, respectfully. She sat on a small wooden stool beneath a cherry blossom tree, a tiny grill puffing white smoke beside her. Spring had come late that year.

The blossoms were heavy, pink and full, petals falling like snow onto the stone path. Her granddaughter sat cross-legged nearby, fiddling with a twig, watching her grandmother turn slices of pork over the flame with the same quiet concentration she brought to everything. “Why do you always grill it like that?” the girl asked. The old woman didn’t answer right away.

She watched the fat sizzle, the edges crisp. The smell drifted upward, curling through the blossoms. When she finally spoke, her voice was low. Because it tastes better over fire, she said. Then after a pause. And because that’s how the cowboys did it. The girl blinked. Cowboys. The word fell like a stone into still water.

It was the first time she’d said it aloud in years, maybe decades. The memory didn’t sting like it once had, but it still shimmerred. too large for sentences. The old woman didn’t explain. She didn’t tell her about Texas or the barbed wire or the guitar music that came at night. She didn’t describe the harmonica that made her cry or the chocolate she kept hidden in her sock for weeks before she dared eat it.

She didn’t talk about the shame of survival or the quiet thrill of tasting cornbread for the first time. She simply said, “Sometimes your enemy feeds you better than your country.” The girl wrinkled her nose, confused, but the grandmother didn’t explain further. She turned the pork again and let the silence settle. It was better that way.

Not every truth needed to be told directly. Some were carried in flavors, in rituals, in the way smoke clung to your clothes long after the fire had gone out. In the years after her return to Japan, the nurse never fully spoke of the camp. When asked, she would say only, “We survived.” But she kept the barbecue sauce bottle tucked in the back of a drawer.

She kept the letters, the ones she never sent, bound with twine, unread but not discarded. When her children asked about the war, she spoke of air raids and ration lines, not of cookouts and cowboy boots. That part she saved for herself. And yet in small ways the story trickled through.

In how she salted her soup, in how she whistled a tune that didn’t belong to any Japanese folk song. In how she insisted on teaching her granddaughter to make fire from scratch without gas. You learn by watching the coals, she’d say, not by rushing them. That too was part of the inheritance. Not just trauma, but tenderness. Not just scars, but sparks. The granddaughter would remember that day, not for the words, but for the feeling. The way the pork smelled.

The way her grandmother’s eyes shimmerred when she said cowboys. the way the smoke drifted through the blossoms like a ghost that didn’t need to haunt only to be witnessed. And someday she too would tell a story, not quite the same, but shaped by it. Because memory doesn’t always come in thunder.

Sometimes it comes in smoke, in the quiet sizzle of meat on flame, in the soft weight of petals on your shoulder, in the way forgiveness blooms, slow, fragile, and impossibly real, like spring after the longest winter.