June 1944. The war in the Pacific had already consumed countless lives when a column of exhausted Japanese prisoners was marched into an American camp. They had surrendered on distant islands, stripped of weapons and stripped of pride. Their bodies lean and brittle from months of hunger.

Many had not tasted meat in weeks, some in months. They expected punishment, humiliation, or at best a thin crust of bread and a bowl of watery soup to keep them alive just enough for labor. Instead, the first shock of captivity arrived not in the form of chains or beatings, but in the mess hall. Inside the wooden structure, long tables stretched from wall to wall, and on them waited trays already filled with food.

The prisoners hesitated at the doorway, their eyes catching the sight and the smell. Thick slices of beef stew glistened in the light, chunks of potato and carrot swimming in gravy. Beside it sat a mound of white bread, a small tin of canned meat, and a spoonful of beans, all steaming hot. An American guard barked in order to move forward, and one by one they filed into line, each handed a tray heavier than anything they had carried from their own army kitchens.

Some could not help but stare. The portion of meat alone was larger than what a Japanese soldier might receive in an entire month of rations. A few men clutched the trays nervously, convinced it was a trick. Their officers had warned them of American cruelty, had said that prisoners would be treated worse than animals, that food would be scarce, that suffering would never end.

Yet here, within hours of capture, they were being handed more nourishment than they had known in years. A young corporal, his uniform hanging loose from his frame, lifted a fork to his lips and tasted the beef. The fat melted across his tongue, the salt and richness overwhelming after months of bland rice balls and dried vegetables.

He almost wept from the shock of flavor, quickly lowering his head so the guards would not see around him. Others devoured their food in silence, while some pushed it away in fear, unable to believe that such abundance was real. The hall filled with the sound of chewing, of spoons scraping trays, of men too hungry to maintain dignity.

Outside the war raged on, but in that moment the prisoners confronted a different kind of battle, one fought not with rifles or bayonets, but with food, a battle they realized their nation could never win. They sat on the wooden benches of the barracks later that night, the taste of beef still lingering on their tongues, and the memories of their lives as soldiers rushed back in waves.

For years, they had been told that the Imperial Army’s strength was built on spirit, that a true soldier needed only rice, miso, and endurance to overcome any hardship. Meat was a rarity, a luxury reserved for special occasions, for officers, or for the sick when supplies allowed. Most enlisted men lived on rice mixed with barley, dried radish, or a handful of pickled plums.

On campaign, the situation worsened. In New Guinea, men had been reduced to scavenging leaves and wild roots, boiling thin soups from whatever they found in the jungle. On Guadal Canal, they ate their last sacks of rice while watching disease consume their comrades. Protein was so scarce that a single piece of dried fish was divided among 10 men.

A rumor of meat rations arriving at the front was greeted like a miracle. But the miracle never came. They remembered carrying heavy packs across mountains with empty stomachs, their steps dragging, their minds dulled by hunger. In the Philippines, soldiers had collapsed on marches, not from bullets, but from starvation. Parasites bloated their bellies.

Tropical ulcers ate through their legs. And yet the army demanded they fight on, declaring that survival was proof of spirit. Letters from home told them their families also lacked food. Wives boiled weeds. Children waited in line for hours for a handful of rice. Even the emperor’s soldiers were not spared the hunger that consumed the empire.

Now in captivity, the comparison was unbearable. The single portion of meat they had been given that afternoon equaled weeks of rations in the field. It was not just the size of the portion, but the idea that this was routine, that the enemy could feed captives with greater abundance than Japan could feed its warriors.

The numbers spoke for themselves. In 1944, American supply chains delivered more than 16 million tons of food to soldiers and prisoners alike. Japanese logistics staggered under shortages. Convoys sunk by submarines and imports cut off by blockade. Where America produced mountains of canned beef, dried milk, and spam by the millions of tons, Japan scraped together rice shipments and foraged whatever it could steal from conquered lands.

The men could not escape the bitter arithmetic. They had been told that spirit outweighed material, that Japanese steel would defeat American decadence. Yet hunger gnawed at them even in their memories, reminding them that no amount of spirit could fill an empty stomach. They looked at their own wasted arms and compared them to the broad shouldered guards who walked past, soldiers who ate meat daily, who carried themselves with the strength of abundance.

For the first time, many of them admitted silently what they could not say aloud. The war had already been decided, not in the jungles or on the seas, but in the fields, factories, and kitchens that produced food beyond measure. The humiliation was sharp. They thought of comrades buried nameless in distant swamps, of officers preaching honor while men died clutching empty stomachs.

And they realized that the empire which demanded their sacrifice had never provided the basic means to sustain them. What they saw on their trays that day was not just food. It was proof. Proof that their army had failed them. Proof that their nation was outmatched by an enemy that considered meat not a luxury but an everyday right. The discovery cut deeper than any battlefield wound, leaving them to wonder whether they had been fighting for a cause already doomed by hunger.

The next morning, the prisoners were marched again into the messaul, the sound of boots echoing on the wooden floor, their breath held tight with expectation and unease. The smell reached them before the sight. roasted meat, onions sizzling, the unmistakable aroma of fat rendered in pans.

When the trays were handed out, some froze in disbelief, beef stew, again, thick with gravy, slices of bread stacked beside it, and a small tin of canned pork. A spoonful of beans, warm and soft, completed the meal. It was not a feast by American standards, but to men who had marched on empty stomachs for months, it was staggering.

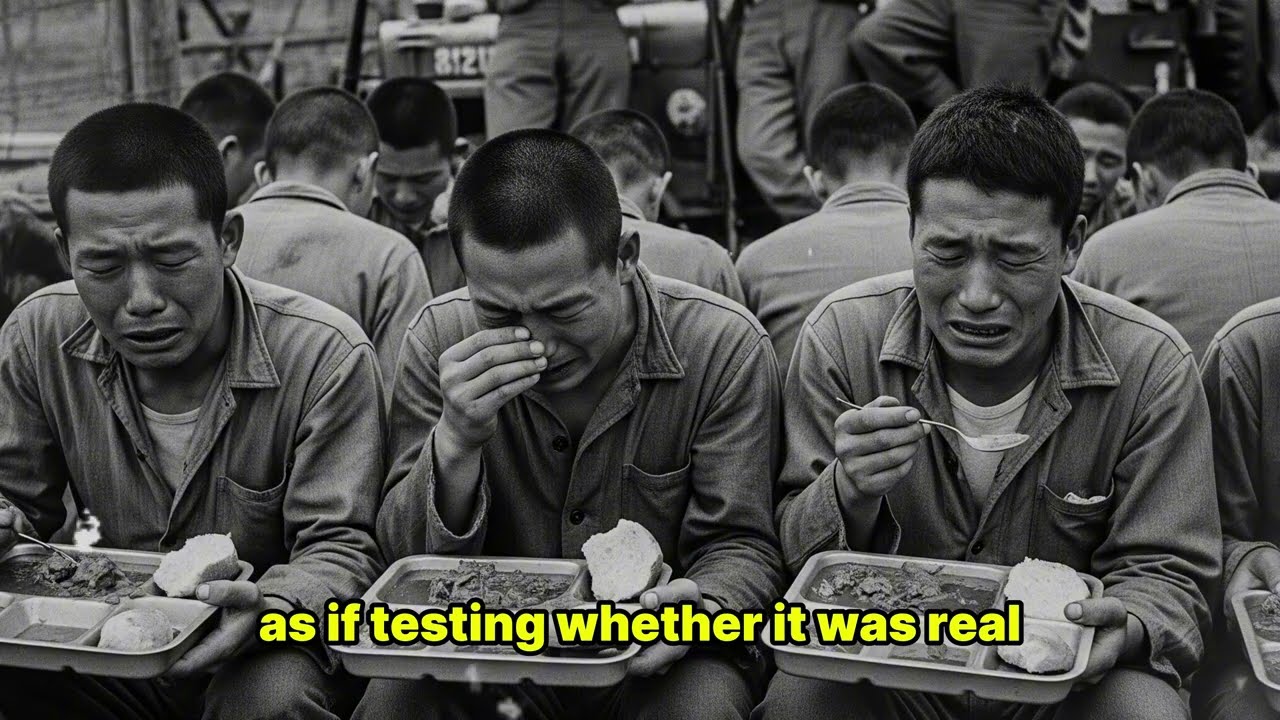

At first, few dared to eat. They stared at the trays as though the food might vanish if touched, or worse, prove to be poisoned. Some whispered that the enemy was fattening them for some cruel purpose. The guards gave no explanation, only gestured impatiently for them to sit and eat. A sergeant with sunken cheeks lifted a fork to his mouth, his hand trembling.

The moment the meat touched his tongue, tears welled in his eyes. He had not tasted pork since leaving Yokosuka 2 years earlier. The salt and richness filled his mouth with a memory so powerful it felt like betrayal. His mother cooking miso soup with a sliver of pork belly. His children chewing hungrily at the table. Others ate more cautiously, breaking the bread into pieces, dipping it into the stew as if testing whether it was real.

One young sailor chewed slowly, his expression blank, but then his face softened, and he devoured the rest in desperate silence. A few could not bring themselves to eat at all. They pushed the trays away, clutching their knees, convinced it was all deception. Hunger wrestled with fear, and fear did not easily let go.

Across the hall, American guards ate their own rations with casual indifference. They chewed, laughed, spoke in voices loud and relaxed. One guard tossed away half a slice of bread without a thought. Another finished only half his portion of beef before rising, tray still heavy with food, and scraping it into a bin.

The Japanese prisoners watched in stunned silence. That discarded meat alone could have sustained a squad for a day on campaign. Here it was thrown away as if it were nothing. The humiliation cut deep. These were men who had once sworn oaths to die rather than surrender, who had believed that the emperor’s soldiers endured hardship as proof of honor.

Now they sat in rows, eating better as prisoners than they ever had as warriors. The irony was unbearable. A corporal whispered bitterly that perhaps surrender was the only path to survival, for in captivity they were treated more humanely than on the battlefield. His words drew glares from older soldiers, but no one could deny the truth.

In the corners of the messaul, whispers spread. Was this America’s true strength? Not in weapons alone, but in the ability to feed even its enemies with abundance. Was this what victory meant? an enemy so wealthy in resources that even waste seemed infinite. The prisoners did not speak loudly. Pride still weighed on them, but the evidence lay steaming on their trays.

Every bite tasted not only of nourishment, but of defeat. They knew in their hearts that this was no temporary gesture, no staged display. This was America’s normal, and that realization was more frightening than any bomb or bullet they had faced. In the weeks that followed, the pattern became impossible to deny.

Day after day, the messaul doors opened, and day after day, trays appeared laden with meat. Sometimes it was beef stew, sometimes pork shoulder simmered until tender, sometimes canned ham or sausage cut into thick slices. But all was more than any Japanese soldier had received in uniform. For the Americans, it was routine, a regulation ration measured in ounces and calories.

For the prisoners, it was a revelation that gnawed at the very foundations of everything they had been taught to believe. They began to learn how it was possible. Guards mentioned names like Hormel and Swift, companies that turned livestock into millions of tins of spam and corned beef each year.

Trains arrived with refrigerated cars. Entire mountains of meat moved across the continent without spoiling. They overheard that the United States had shipped nearly 100 million cans of spam across the world to Europe, to Africa, to islands scattered in the Pacific. The numbers staggered them. One can weigh a pound.

A 100 million pounds of meat, just one product. And America treated it as a convenience. They compared it to their own experience. In the Japanese army, supply officers fought over sacks of rice, scratching out allocations with shaking hands, knowing there was never enough. Soldiers boiled river water to soften roots and weeds.

Meat was almost mythical, spoken of in longing. Even officers rarely saw it except on holidays. Now they realized that while they had been rationed to near starvation, America’s factories had been churning out an endless flood of calories. Historians would later note that in 1944, American agriculture produced over 100 billion pounds of meat.

The sheer scale was beyond comprehension. Even if half were wasted, it would still dwarf Japan’s entire national output. To the prisoners, the realization was unbearable. They sat with trays balanced on their knees, chewing mechanically. But in their minds, they saw the contrast. They remembered comrades who had died with bellies shrunken, skin stretched over bone, men who had perished not from bullets, but from hunger.

Now they ate as those men never could, and the shame tasted as strong as the beef itself. The guards treated the process with indifference. They handed out trays, filled pots, and moved the line forward as though feeding thousands was no effort at all. For them, it was procedure, a duty carried out without thought.

For the prisoners, it was a constant reminder that America’s war machine was not only guns and planes, but fields, railroads, factories, and supply chains that could carry a cow from Kansas to a prisoner’s tray in a matter of days. The enemy had made food into a weapon, and the weapon was devastating. One evening, as the prisoners shuffled back to their barracks, an older sergeant muttered under his breath that Japan had lost the war the moment it declared it could survive on Spirit alone.

His comrades said nothing, but no one contradicted him. The evidence was too clear. Spirit did not produce meat. Spirit did not feed an army. It was industry, cold and relentless, that decided who would endure and who would starve. Each new meal drove the lesson deeper. America could afford to make abundance seem casual. Japan could not even feed its fighting men.

It was not only their bodies that were being nourished in captivity. It was their illusions that were being stripped away, one tray at a time. At first, the prisoners thought the endless meat was meant to humiliate them, a cruel trick to remind them of what they had been denied. But as the days turned into weeks, the pattern never changed.

Breakfast brought bacon or sausage with eggs. Lunch brought sandwiches thick with ham, and dinner was almost always heavy with beef or pork. The abundance no longer felt like a performance. It was routine, impersonal, the way guards distributed rations without ceremony, as if such portions were nothing remarkable.

That realization cut deeper than any taunt. For Americans, this was simply normal life. For the prisoners, it was a daily reminder of how little their own nation had provided. Sitting in long rows on the benches, many whispered about the comrades they had lost in the jungles and on the islands. They remembered men who had wasted away on handfuls of rice, who had died scratching at their skin for food, who had eaten grass to quiet the pain of hunger.

Now they chewed tender beef, and the taste filled them with shame as much as nourishment. Some admitted in low voices that they had never eaten so well, even in peaceime Japan. Others laughed bitterly, saying the Americans were mocking them by feeding them better as prisoners than as soldiers. The humiliation spread silently through the camp.

A corporal from the Philippines campaign confessed that he had eaten meat fewer than 10 times in four years of service. Now it was placed before him daily by the enemy. He pushed his tray away in anger one night, but hunger soon forced him back. A sergeant, his cheeks sunken from malaria, muttered that the emperor had abandoned them, that the true strength of an army lay not in spirit, but in supply.

His words drew glares, but no one contradicted him. The contrast grew sharper when they watched the guards. American soldiers ate without reverence, chatting casually, often leaving food half-finish. One threw scraps to a stray dog outside the mesh hall. The prisoners stared at the animal devouring meat that they would once have killed for.

The thought burned in their chests. To the Americans, meat was so plentiful that even a dog ate better than Imperial troops. Nights in the barracks were filled with uneasy silence. Men lay awake, staring at the rafters, listening to their stomachs digest food they never believed they would taste again. The taste of meat, rich and heavy, lingered on their tongues as a bitter reminder.

It was proof of defeat served on a metal tray. They had marched across Asia, believing that endurance and sacrifice would carry them to victory. Now they knew the truth. Their leaders had sent them into battle with empty stomachs against an enemy whose strength flowed not only from factories and shipyards, but from kitchens and fields.

The shame was unbearable. Some prisoners wept quietly into their blankets. Others clenched their fists in silent rage. A few whispered prayers for their fallen comrades, ashamed that they were alive and eating while the dead had starved in service to a cause that had never cared for them. In the mess hall each day, as meat was ladled onto their trays, they felt the weight of their empire’s failure.

It was not just their bodies that were being fed. It was their pride that was being devoured bite by bite until nothing remained but the bitter knowledge that Japan could never match such power. The comparison between the two armies became impossible to ignore. Every time the prisoners lined up for meals, they saw the guards who served them.

Broad shoulders, full faces, steady eyes. The Americans looked nothing like the gaunt figures who had marched under the rising sun. The difference was not only in uniforms or weapons. It was carved into flesh and bone. The average American soldier stood taller by more than a head, weighed 20 kg more, and carried himself with the confidence of a man who had never known true hunger.

The prisoners felt the contrast every time they caught their own reflections in puddles or tin cups, hollow cheeks, sunken eyes, ribs pressing against thin skin. The statistics told the same story. In 1944, American rations averaged over 4,000 calories per day, including nearly a pound of meat. Japanese rations rarely reached 2,000, and much of that was rice or barley.

Protein was scarce, vitamins nearly absent. In the field, shortages reduced the numbers further until many soldiers survived on less than 5,200 calories a day. It was not a battle of equals. It was a battle between men who were fed to fight and men who were starved into weakness.

The prisoners remembered the endless lectures of their officers. They had been told that spirit was greater than strength, that the will to endure could conquer any hardship, but the evidence before their eyes told another truth. A man with full muscles and steady blood could march farther, fire straighter, and recover from wounds faster than a man with nothing in his belly.

The guards they watched every day were living proof. They carried rifles effortlessly, their boots polished, their posture straight. Even their laughter sounded strong. One prisoner, a young sailor captured at Saipan, whispered that he finally understood why the Americans always seemed unstoppable. It was not just their ships or planes. It was the fuel in their bodies, the endless supply of meat and milk and bread that gave them stamina.

Another, an older veteran from China, admitted with bitterness that Japan had sent its soldiers into battle like farmers, sending oxmen to die of exhaustion, while America had treated its soldiers like investments, feeding them to ensure victory. The humiliation deepened as memories returned. They recalled comrades too weak to carry rifles, men collapsing during marches, units crippled not by bullets, but by malnutrition, diseases spread through camps where lice and hunger gnawed at men’s strength until they were shells. Now in

captivity, their wounds healed faster, their coughs faded, their bodies filled with strength they had not known in years. The realization was unbearable. Their enemy had given them more dignity in defeat than their own leaders had granted in service. At night, when the barracks settled into uneasy silence, the thought circled in every mind.

This was not about honor or spirit. It was about numbers, calories, and logistics. They could feel the truth in their own recovering bodies. For the first time, many admitted silently that the empire they had fought for was never capable of winning. The Americans had turned food into a weapon more powerful than any rifle, and the war had been lost the moment Japan chose starvation over supply.

Night fell heavy over the camp, the silence broken only by the creek of wooden bunks and the restless shifting of men who could not sleep. The air smelled faintly of soap and cooked meat. sense that still felt foreign in their nostrils. On those nights the whispers began, low and uncertain, like men afraid of their own voices.

Why did the Americans feed them so well? Why waste meat and bread on enemies? Some argued it was a trap, a form of warfare disguised as kindness. A corporal muttered that the fat in their food was poison meant to weaken them slowly. Another insisted that America wanted to shame them, to break their warrior spirit by showing them how little their own nation had provided.

Yet the days passed, and the rations did not change. Each morning brought bread and butter, each evening meat and potatoes. The food healed their wounds, filled their hollow stomachs, and gave them strength they could not deny. Suspicion clung stubbornly, but hunger gnawed harder. A sergeant who had sworn never to touch American food finally gave in after 3 days, devouring his portion with tears streaming down his cheeks.

That night he whispered to his bunkmate that he had never eaten so well, not even in his childhood. The shame of that admission hung in the air. These were men who once believed that to endure hunger was proof of honor, that to march on empty stomachs was a badge of courage. Now they ate until their bellies were full, and the realization struck with cruel clarity.

The empire they had fought for had abandoned them. The enemy gave them more in captivity than Japan had given them in loyalty. In the messaul, the humiliation sharpened with each glance at the guards. American soldiers tossed halfeaten bread into trash bins, poured unfinished coffee onto the ground, left plates stre with grease and gravy.

To them, waste meant nothing. To the prisoners, every crumb was a memory of comrades who had died clutching empty stomachs. One man clenched his fists until his knuckles bled, whispering that the dog he had seen outside the fence ate better than an Imperial soldier. That night in the barracks, a long silence stretched after the evening meal.

A lieutenant who had once preached sacrifice spoke quietly, almost to himself. “We lost long before we surrendered,” he said. “No one argued. The truth was written in their filled stomachs and the quiet shame that settled over them. For the first time, many understood that the war had been decided not by the clash of fleets or the courage of men, but by the steady, relentless power of supply.

Spirit alone could not fill a bowl. Spirit could not march without strength. And spirit, no matter how fierce, could not change the taste of defeat served hot on an American tray. Years later, survivors would say that the moment they truly understood defeat was not on the battlefield, but in the camp dining hall.

The memory of that first heavy tray never faded. One prisoner, gay-haired in his old age, recalled how he stared at the meat steaming before him, unable to lift his fork. In that instant, he said, “I knew Japan had already lost. An empire that could not feed its soldiers could never stand against a nation that fed even its prisoners like kings.

His voice trembled with both shame and awe, for the truth had cut deeper than any wound. The lesson became clearer with each passing week. Their bodies healed. So closed, coughs faded, strength returned. The food that once felt like humiliation turned into undeniable evidence of power. The Americans did not feed them to mock them.

They fed them because abundance was the natural condition of their war machine. Behind every slice of beef stood factories running day and night, railroads hauling refrigerated cars across thousands of miles, farms that produced so much grain and cattle that waste meant nothing. Behind every loaf of bread was an industrial system so vast that it could extend comfort even to sworn enemies without hesitation.

The prisoners realized then that they had not been fighting equals. They had been pawns in a struggle already decided by numbers. Their commanders spoke of honor, but honor could not conjure meat from empty fields. Their leaders demanded sacrifice, but sacrifice could not build refrigerated ships or produce millions of cans of rations.

The empire had demanded loyalty while starving its soldiers while the enemy poured rivers of food across oceans without pause. At night, in the silence of the barracks, many confessed to themselves that they had been deceived. They remembered the propaganda. Americans were decadent, weak, incapable of hardship.

But in captivity they saw the opposite. Decadence had not weakened America. Abundance had made it unbreakable. Its soldiers marched with full stomachs, fought with strong bodies, and never doubted that another meal awaited them. The prisoners, by contrast, had been taught that hunger was proof of strength, that endurance of suffering was noble.

Now they understood that it had only been desperation masquerading as virtue. The revelation was as bitter as it was undeniable. Spirit alone could not win wars. Discipline without supply was a hollow shell. They had fought for a cause that glorified sacrifice, but neglected survival, and it had cost them everything.

In the end, the taste of defeat was not gunpowder or blood. It was beef stew ladled into a tin tray, steam rising in a foreign camp. Proof that the empire of Japan had been broken not by the will of its enemies, but by the cold mathematics of industry, logistics, and food.