September 12th, 1945, Fort Sam Houston, Texas. The morning sun beat down on the repatriation center with a heat that turned the air thick and shimmering. Inside the messaul, a group of Japanese women, civilian internees, recently transferred from camps across the Pacific, sat before steaming plates of food they would not touch.

The beef sat untouched, growing cold. American officers watched with confusion turning to frustration. These women had survived years of war, months of displacement, and weeks of uncertainty. Yet here, offered abundance, they chose hunger. The cultural worker assigned to them spoke softly in Japanese, gesturing to the food. Still, they would not eat.

And in that moment of stubborn refusal, neither side understood they were standing at the crossroads of two worlds that had spent 4 years trying to destroy each other. Before we continue with this remarkable story, if you’re fascinated by these untold moments from World War II, hit that like button and subscribe to keep these stories alive.

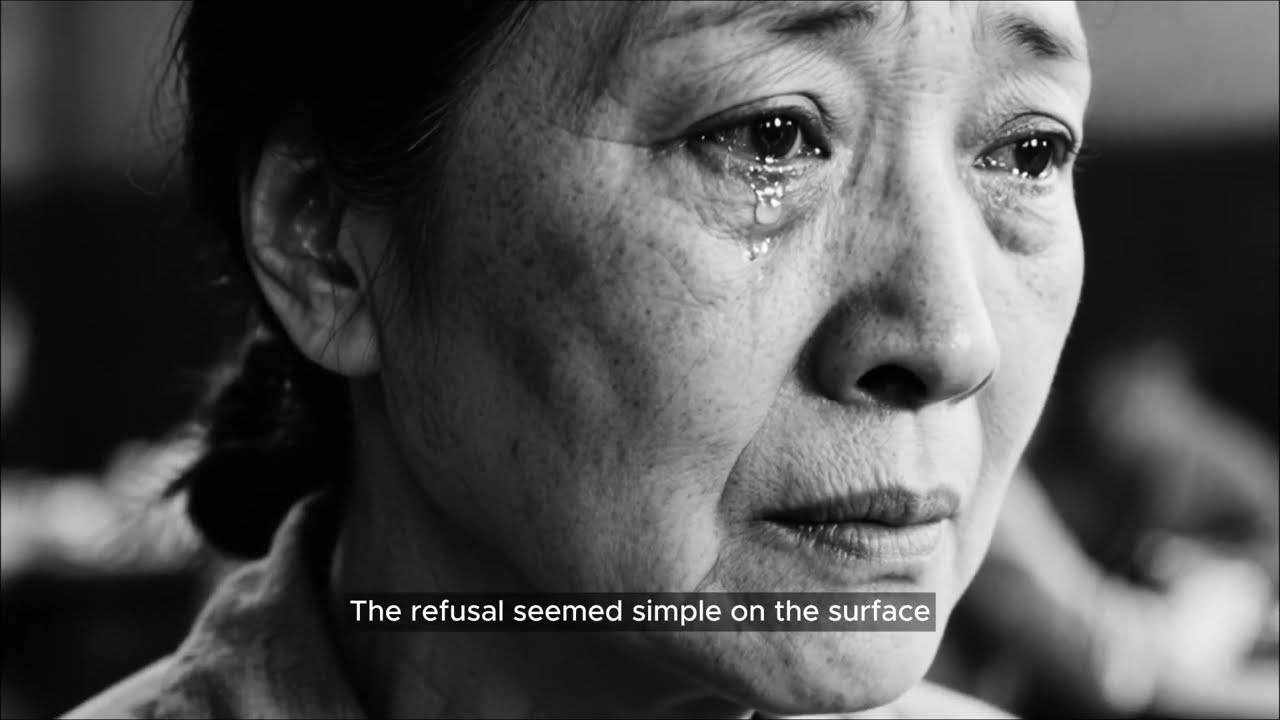

Drop a comment telling us where you’re watching from. We love hearing from our community around the globe. Your support helps us bring more forgotten history to light. The refusal seemed simple on the surface, but what happened next would reveal something profound about occupation, identity, and the strange mathematics of surrender.

Because when these women finally understood what they were being offered, their tears would tell a story no treaty could capture. To understand why beef became a battlefield, you must first understand who these women were and how they came to be in Texas at all. Between 1942 and 1945, the United States interned approximately 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry on American soil.

But across the Pacific, a different population faced displacement. Japanese civilians caught in war zones as American forces island hopped toward the home islands. Missionaries, teachers, nurses, merchants, wives, women who had followed the empire’s expansion into Manuria, the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies. When those territories fell, they became prisoners of war.

Some spent years in camps in Australia and New Guinea. Others were held in the Philippines under conditions that varied from austere to brutal. By war’s end, thousands needed repatriation. The logistics were staggering. Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio became one of several processing centers. The facility had served as a military post since 1876.

Had treated Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders after the SpanishAmerican War. had grown into a sprawling complex of barracks and administrative buildings. In September 1945, it transformed into a way station between war and whatever came next. The women who arrived there carried nothing but what they’d been allowed to keep.

A photograph, a letter, sometimes less. They had survived the war. But survival had cost them everything familiar. Language home. the assumption that tomorrow would resemble yesterday. American authorities faced an unexpected problem. These women were not enemy combatants. They were not criminals. They were civilians who had committed no crime beyond being Japanese in the wrong place when the war started.

The Geneva Conventions offered little guidance. So the US military defaulted to practicality. house them, feed them, process their paperwork, send them home. The Messaul staff prepared standard American military fair. Roast beef, mashed potatoes, green beans, coffee, the same meals that fed the tens of thousands of soldiers processing through Fort Sam Houston.

But on that September morning, when the first group of women entered the cafeteria, they saw the sliced beef and recoiled. The cultural liaison, a second generation Japanese American woman named Grace Nakamura, who had volunteered for the War Relocation Authority, recognized the problem immediately. She had seen it before in the internment camps in California.

Buddhist dietary restrictions, religious taboss, cultural norms that ran deeper than hunger. She tried to explain to the mess sergeant, “They won’t eat beef. It’s against their beliefs. The sergeant, a career soldier named William Tucker from Georgia, stared at her in disbelief. “Ma’am, we got plenty of beef. It’s good beef.

We ain’t serving them scraps. It’s not about quality,” Grace said quietly. “It’s about religion.” But she was only partially right. The truth was more complicated. In traditional Buddhist practice, the consumption of beef carried particular stigma. Cattle were working animals, partners in rice cultivation, essential to agricultural life.

To kill and eat them violated principles of compassion and practical necessity, both this prohibition had softened in Japan over the decades. The Maji restoration in the late 1800s brought Western influence and dietary changes. By the 1920s, beef consumption existed in Japanese cities, though it remained uncommon in rural areas.

The military itself served beef to soldiers, framing it as modern, western, powerful, but among women of a certain generation, particularly those from traditional backgrounds. The taboo persisted, not universally, but commonly enough that Grace Nakamura’s explanation made sense to her superiors. The problem was what to do about it.

The military operated on standardized rations. Substituting meals for dozens of women created logistical headaches. Besides, the women would be at Fort Sam Houston for weeks, possibly months, while their repatriation was arranged. They could not simply skip meals indefinitely. Colonel Arthur Morrison, the officer overseeing the repatriation program, called a meeting.

He was a pragmatic man, 53 years old, who had spent the war managing logistics in the Pacific theater. He had coordinated airlifts and supply chains across thousands of miles of ocean. Surely, he could solve the problem of feeding some civilian interneees. What do they eat? He asked, “Grace, rice, fish, vegetables, miso, soup, tofu.

” Morrison wrote this down. “We can do fish. We can do rice. The vegetables we’ve already got.” And for the next week, that’s what the women received. Grilled fish, steamed rice, carrots, and beans. The meals were bland by Japanese standards, lacking the complexity of dashi broth and proper seasoning, but they were acceptable.

The women ate, but then the fish supply ran short. The commissary had other priorities. Thousands of soldiers moving through Fort Sam, Houston, hospital patients, administrative staff. Morrison made calls. He pulled strings. But in midepptember 1945 with millions of men demobilizing across the globe, fresh fish in San Antonio, Texas was not a priority for anyone.

The mess sergeant approached the colonel with an idea. Sir, what if we don’t call it beef? Morrison looked up from his paperwork. Excuse me, what if we tell them it’s something else? Something they’d be willing to eat. Sergeant, I’m not going to lie to these women about what they’re eating.

Tucker shifted his weight. Not lying, sir, just presenting it different. You know how back home we got 100 ways to cook a pig? Well, Texas has 100 ways to cook a cow, and some of them don’t look nothing like beef. Morrison leaned back in his chair. Go on. What Sergeant Tucker proposed was not deception exactly. It was translation.

Texas barbecue, specifically the central Texas style that dominated San Antonio, transformed beef into something else entirely. Brisket smoked for 12 hours became tender, dark, almost unrecognizable as the roasts the women had been refusing. Sliced thin, served with sauce, it bore little resemblance to the pink slabs that had repulsed them.

Tucker had grown up outside Austin, where his father ran a smokehouse. He knew barbecue the way some men knew scripture. He understood that smoke and time could transform the toughest cuts into something approaching transcendence. He proposed a test. The next morning, he arrived at the messaul at 4:00 a.m. He had requisitioned a brisket, 14 lb of beef, fat cap intact.

He trimmed it, seasoned it with salt and pepper, nothing fancy. He lit the smoker behind the mesh hall, adjusted the airflow, settled in to wait. By noon, the smell had spread across the entire repatriation center. Sweet oak smoke carrying the promise of something primal and good. Soldiers stopped to ask what was cooking.

Administrative staff found excuses to walk past the messaul. At 400 p.m., Tucker pulled the brisket. The bark had formed perfectly, dark and crusty. The meat beneath was pink rimmed and tender. He let it rest, then sliced it thin across the grain. Each slice revealed the smoke ring, the marbling, the transformation that heat and patience had wrought.

He plated it simply. sliced brisket, a small cup of sauce on the side, white bread, pickles, kleslaw. Grace Nakamura looked at the plate. “What am I supposed to tell them? This is Texas barbecue,” Tucker said. “That’s not a lie. That’s what it is.” She studied the meat. It did look different. The smoking process had darkened it, changed its texture.

It no longer resembled the pale roast beef that had caused the initial refusal. That evening, Grace brought the plate to Kimiko Tanaka, the informal leader among the women. Kimiko was 47 years old from Osaka, a doctor’s widow who had spent 3 years in a camp in New Guinea. She spoke some English. More importantly, she commanded respect.

Grace explained that the Americans had prepared a special Texas dish, regional specialty, smoked meat, very different from the beef served before. Kimiko studied the plate with suspicion. She lifted a slice, examined it, smelled it. The smoke had indeed transformed it. This did not look like any beef she had encountered. The texture was different.

The color was different. The smell was entirely different. Woods smoke and char and something almost sweet. She took a small bite. The other women watched in silence. They had learned to read each other’s faces across language barriers and shared hardship. They watched Kimiko chew slowly, consideringly.

Then she took another bite. Larger this time. O shei, she said quietly. Not beef, something else. Texas barbecue. The distinction mattered. In their minds, they were not abandoning their principles. They were encountering something new, something that existed outside the categories they knew. Barbecue was not beef the way a butterfly is not a caterpillar.

The transformation made it permissible. Over the next week, Tucker smoked brisket every other day. The women ate their health improved. The tension in the messaul eased. Morrison filed reports noting that the dietary situation had been resolved through culturally appropriate food preparation. But something else was happening too.

Something the reports didn’t capture. The act of eating barbecue became a ritual of transformation for the women. They were in the heart of Texas in the nation that had defeated their empire. Eating food that was quintessentially American in a way that transcended simple patriotism. Barbecue was regional identity made edible.

It was the convergence of German and Czechmeat smoking traditions, African-American cooking techniques, Mexican influences, all filtered through the particular teroir of Central Texas. To eat it was to participate in American culture at its most fundamental, not formal, not imposed, simply shared. One afternoon, Tucker showed a small group of women the smoker.

Through Grace’s translation, he explained the process, the wood selection, post oak, not mosquite, for brisket, the temperature control. The patients required 12 hours minimum, sometimes 16. The women listened with the attention of people who understood craft. Several had come from farming families. They knew what it meant to work with time and temperature to coax transformation from raw materials.

One woman, Yuki Hamada, asked through grace whether the meat was expensive. Tucker laughed. Ma’am, brisket used to be the cheapest cut you could buy. Folks didn’t want it, too tough. Then somebody figured out if you smoke it low and slow, it turns into something special. Now it’s popular, but it’s still workingclass food.

Food for regular folks. This information changed something in how the women perceived the meal. They were not being served luxury to impress them. They were being served the food that ordinary Americans ate, prepared the way ordinary Americans prepared it. There was a democracy in that, a kind of respect. By late September, the situation had settled into routine.

The women ate barbecue twice a week, fish and chicken the other days. They were gaining weight, recovering from years of inadequate nutrition. The medical staff noted improvements in energy, mood, overall health. But then Kimikot Tanaka made a request through Grace. She wanted to know what meat they had been eating. The question came during dinner.

Grace had been sitting with the women, helping translate announcements about repatriation schedules, Kimiko asked casually as if the question held no particular weight. Grace hesitated. She had been part of the tacid agreement not to emphasize that barbecue was beef. Not deception exactly, but careful presentation. She looked around for Morrison or Tucker, but neither was in the mesh hall.

“It’s smoked beef,” she said finally. “Brisket from a cow.” The women at the table went silent. Several put down their forks. Kimiko stared at her plate. Then, unexpectedly, she laughed. It started as a chuckle, then grew into something fooler, tinged with irony and resignation. Several other women joined her. We knew, Kamiko said in English.

Her accent was heavy but clear. We knew. Grace blinked. You knew. Since when? Maybe second time. Maybe third. Beef is beef. Kimiko gestured at her plate. But this is not war beef. This is peace beef. The distinction she drew was not culinary. It was existential. The beef they had refused was the beef of their defeat. Served plainly without ceremony, it represented everything they had lost.

Their country had been beaten. Their world had ended. To eat that beef would be to accept their defeat with nothing in return but calories. But barbecue was different. Barbecue was craft. It was patience. It was the application of skill to transform something tough into something tender. To eat it was not surrender.

It was participation in a ritual that acknowledged their humanity. They had not been defeated by barbecue. They had been invited to share in it. The distinction might seem subtle, but it reflected a profound truth about occupation and identity. In the immediate aftermath of World War II, millions of people faced the question of how to live in a world their side had lost.

For Japanese civilians, this was particularly acute. Their nation had been built on the mythology of divine protection, of cultural superiority, of inevitable victory. The atomic bombs had shattered those myths literally and figuratively. How did one proceed after such total defeat? The women at Fort Sam Houston were navigating this question in the most basic terms.

What to eat? Whether to eat? Each meal was a small decision about whether to accept the world as it now existed. The initial refusal of beef was not about dietary law. It was about maintaining some threat of control, some boundary between themselves and their capttors. The beef represented everything they could no longer afford to be.

But barbecue offered a different framework. It was not imposed. It was shared. Tucker had not served them standard military rations and demanded they eat. He had prepared something specific, regional, particular. He had extended craft and care that made acceptance possible. Over the weeks that followed, something remarkable happened.

The women began asking questions about Texas, about American food, about the lives of the soldiers and staff around them. The barbecue had opened a conversation that formal repatriation procedures never could. Grace found herself translating discussions about cattle ranching, about Mexican influences on Texas cooking, about the differences between southern barbecue styles.

The women absorbed this information with genuine curiosity. They were perhaps without fully realizing it, beginning to construct a new understanding of the nation. This was not Stockholm syndrome or propagandainduced affection. It was something more subtle. It was the recognition that American power was not purely military.

It was also cultural, industrial, agricultural. The ability to turn the toughest cut of beef into something delicious was in its own way a demonstration of the same problem-solving capacity that had built the B29s and coordinated the Pacific campaign. One evening, Yuki Hamada asked Tucker through grace whether Japanese people could make Texas barbecue.

Tucker considered it. Don’t see why not. You need a smoker, wood, patience, and decent meat. Rest is practice. In Japan, we have no cattle like this, Yuki said. Then adapt. Use what you have. That’s how barbecue works. Every region does it differently because resources differ. This seemed to satisfy Uka recognition that barbecue was about adaptation, making do, transforming what you had into something better.

In early October, Morrison learned the women would depart for Japan in 2 weeks. He called Tucker and Grace. I want to do something for them before they leave. Appropriate. Grace understood immediately. A barbecue, a proper one, an event. Tucker nodded. Morrison approved. Three brisketss, two pork shoulders, chicken, sausage were requisitioned, and other cooks recruited.

Behind the messaul, six smokers ran enough to feed the women and the repatriation staff. On October 10th, 1945, Fort Sam Houston held a cultural exchange dinner. Texas’s most unusual barbecue. The women arrived uncertain, found long tables outdoors, smokers smoldering, soldiers serving brisket, pulled pork, smoky chicken, sides of salad and beans, sweet tea, and lemonade.

For the first time, they ate without hesitation. Kimiko stood. Grace translated, “We thank you. You treated us as people, not enemies.” Tucker nodded. The women departed October 24th. Carrying little but a story of food, care, and transformation. Yuki opened a restaurant. Grace reflected on cultural meeting.

Tucker ran his smokehouse. Peace began with smoke and barbecue.