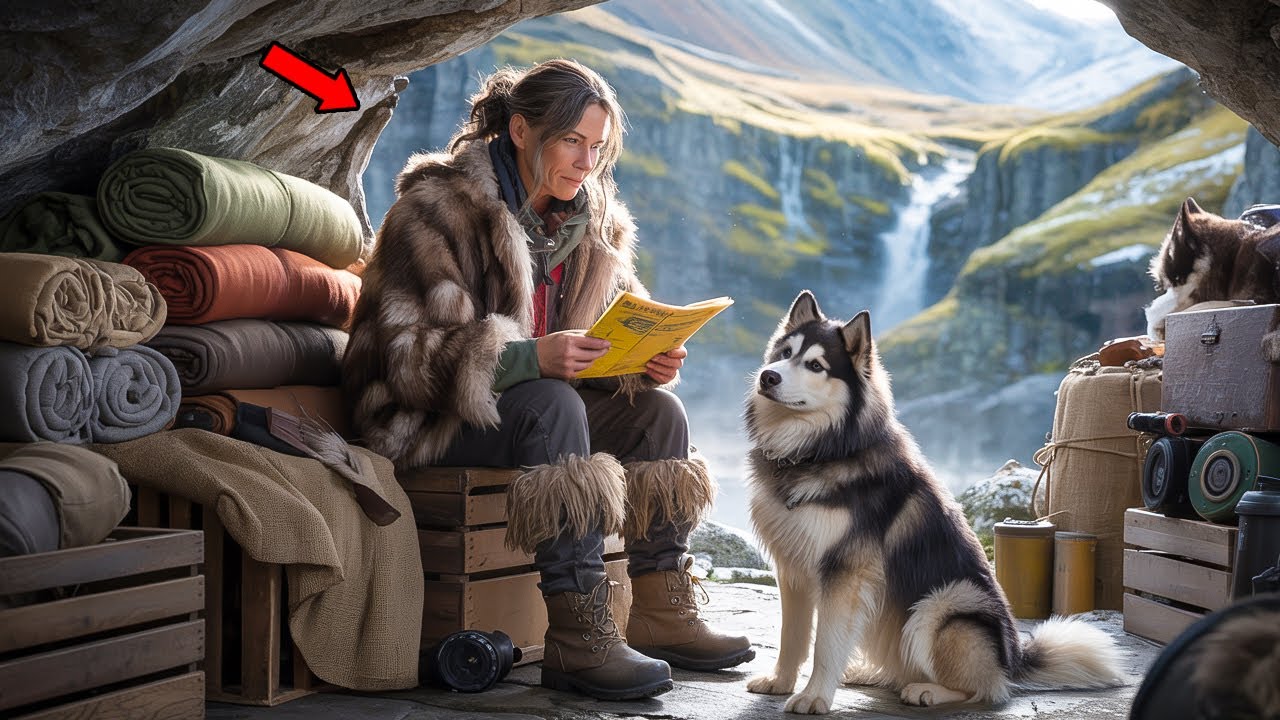

Some people say animals don’t keep secrets, but those people never met Hazel Emberwood, and they certainly never met her dog, Juniper. Hazel was 68 years old, and she lived alone in a cedar cabin high above Cloudstep Ridge, a place where winters stuck around like nosy relatives, and summers arrived too shyly to be noticed.

She’d spent the last 22 years bringing the same quiet gifts to her days, gathering firewood, tending the herb patch she claimed healed, anything short of heartbreak, and talking to Juniper as if he were a bearded neighbor instead of a dog. Juniper wasn’t just any dog. He was half husky, half mountain, who knows what, with silver fur and golden eyes that always seemed to be one step ahead of her.

He had discovered where every grouse nest lay, which apple tree produced the sweetest fruit, and which hikers were about to slip on loose slate before they even lifted a boot. Hazel told him he had grandmother senses, a term Juniper did not appreciate, judging by the offended snorts. Before we carry on, please hit the subscribe button to make my day, and let me know where you are watching from in the comments.

Life at Cloudstep Ridge was simple and quiet. Hazel liked it that way. After a long life of trying to fit into town expectations, husband, job, church on Sundays, potluck on Tuesdays, solitude felt not like loneliness, but like oxygen. She made tea at dawn. She collected water from the creek before the sun cleared the eastern peaks.

She checked the vegetable garden, the wood pile, and the wind turbine that groaned whenever it wanted attention. And above all, she trusted Juniper to warn her when anything unusual happened. Which is why when Juniper began sneaking out every morning and returning 2 hours later smelling suspiciously of creek water and pine sap, Hazel paid attention.

At first, she assumed he had found a particularly flattering rock to nap on. Dogs were vain like that. But then one morning, he disappeared before tea even boiled. He trotted down the valley trail with his tail stiff, purposeful, nose in the wind like a professional courier on an urgent errand.

Hazel watched him go, eyebrows lifted, “Well,” she muttered, “I suppose you’ve joined a club.” By the fifth day of secretive disappearances, she packed a satchel flask of tea, two sandwiches, and a pair of binoculars older than certain national highways. When Juniper trotted off at sunrise, she followed. The air was cold and clean, and the path was messy with roots.

Hazel hiked slowly, knees complaining, heart steady. She used to say her knees were like two old roommates who no longer liked one another, but still lived together for convenience. Juniper moved with steady, eager strides. He didn’t look back until they reached a stunted patch of junipers growing beside a mossy boulder.

He paused, glanced over his shoulder, and waited. “So now you care about me?” Hazel puffed, leaning on her walking stick. Juniper wagged his tail once as if to say, “Yes, hurry up. Important business.” He led her through a ribbon of trees she had never explored. Hazel had lived here for decades, but the mountains always kept secrets until you proved worthy of them.

Beneath the canopy, sunlight broke into green shards. The smell of wet stone and cold water sharpened. And then she heard it. A sound like falling beads, like wind through crystal strings. A waterfall. Juniper bounded forward. Hazel followed. Boots squishing into damp moss. The trees parted into a clearing carved by nature’s own hands.

A fall of water poured from a stone lip 10 m above, catching sunlight like a handful of diamonds tossed through the air. Behind the waterfall, the cliff face dipped back. Not a cave exactly, but a deep pocket hidden by water and shadow. Juniper darted behind the curtain of water. Hazel thought she must be losing her mind because she said aloud, “Oh, for goodness sake, you’ve discovered Narnia.” She gingerly stepped through the freezing spray.

Her coat soaked instantly, her boots squealled in protest, and her hair snapped into curls that would require serious negotiation with a comb later. But on the other side, she found something impossible. Not treasure chests or duffel bags full of gold bars like in movies, but an arrangement. Storage crates stacked neatly, some wrapped in oiled canvas.

Several sealed tins and old-fashioned cantens sat on a shelf hacked from the cave wall. A lantern hung from a rusted hook. The place wasn’t wild or accidental. It was intentional. Her pulse hiccuped. This was a cash. A real one. Hazel knew about cashes. Her father taught her the ways of mountain people when she was a girl.

Never hide what you can’t afford to lose, he’d said. And never touch a stash unless it’s yours or someone is in danger. Saddens. She approached slowly. Juniper sat beside a wooden crate, tail wagging, eyes bright. Hazel could practically hear him thinking. Well, aren’t you going to open it? Oh, yes, Hazel muttered.

Let me just break the sacred rules of mountain folk and start rumaging in some bandits old pantry. Still, her hands wandered toward the lid. She lifted it gently. Inside, wrapped in waxed cloth, lay objects she didn’t recognize. Leather pouches a tin of dried herbs labeled in handwriting older than her, and most unsettling, a small envelope sealed with cracked red wax. On the outside in dark ink were the words for Hazel Emberwood.

When she is ready, Hazel froze. Her name not Hazel, not H. Emberwood, not to the finder. Her full unmistakable name. Juniper shifted, pressing close against her leg. Hazel swallowed. The wind outside the waterfall hissed like a whisper. Juniper, she said softly. I think someone has been waiting a very long time for me.

She sat on a stone ledge, turned the envelope in her hands, and listened to the water thundering like distant applause. There was only one person she had ever known who wrote with such looping, careful strokes. Her great aunt Clementine, the woman her family only spoke of in muttered warnings and family gossip, the mountain woman who vanished decades ago after a scandal involving land rights and a missing inheritance. Hazel broke the wax seal.

Inside were two things, a folded letter and a photograph of Clementine as a young woman standing beside a dog who looked remarkably like Juniper. She whispered, “Oh dear, your family. It’s Juniper sneezed in agreement.” Hazel read the first line of the letter. “If you found this place, then the mountains have decided you’re worthy.

Not everyone gets to know the truth.” Her heart thutdded gently like a wooden spoon tapping a pot. She read on, “The truth, it seemed, was only beginning.” Hazel never liked dramatic pauses. She believed life was messy enough without deliberate cliffhers. Yet here she was, sitting behind a waterfall, soaked like laundry in monsoon season, holding a letter that seemed very determined to deliver one dramatic revelation after another.

Juniper nudged her knee, encouraging in the way only a dog could be. “Read. Breathe. Don’t faint. Preferably, don’t drop treats on the ground.” Hazel took a steadying sip of her lukewarm tea and unfolded the letter. “Dear Hazel, if you’re reading this, then the mountains have found you capable. I know that sounds poetic and possibly unhinged, but trust me, Cloudep Ridge doesn’t let just anyone wander into its secrets. It allowed me and now it has allowed you.

I am Clementine Emberwood. Though I suspect you already guessed. You might have heard stories, wild ones. They are mostly untrue. The truth is simpler. I left because people misunderstand mountains. They think they give gold when really they give wisdom. They think they are protectors when really they are teachers.

There is something here that needs protecting, something only an emberwood can guard. Hazel blinked. Wonderful, she muttered. A prophecy, and here I am without a proper hat, she continued reading. The cash you found is only the first. I gathered supplies and tools for whoever would follow because I knew I would not live long enough to solve everything. There are three more cashes hidden across the ridge.

Together, they form a legacy not of money, but of responsibility. Begin by speaking to a woman named Meera Fernwood. She lives in the valley town of Alderbridge, owns the seed shop, and knows how to listen to trees. She knew me well, and she will know what comes next. Trust your instincts. And trust the dog, Clementine.

Hazel read the final line twice. Trust the dog, Hazel turned to Juniper. Well, she said, “I can’t argue with that part. Better than trusting my knees.” She tucked the letter into her satchel along with the photograph. the other contents she left untouched.

The mountain may have chosen her, but she wasn’t about to start rearranging someone’s sacred stash like it was a spice cabinet. On the hike back, the valley stretched below like a stitched quilt of evergreens and little squares of farmland. The wind tugged at her coat, not fierce, but insistent, like a child reminding their grandmother she’d forgotten her reading glasses again.

Halfway up the slope, her knees produced the familiar duet of creeks and snaps. Juniper paused, “Waiting.” “You’re not subtle, you know,” Hazel told him. Juniper wagged once, unimpressed by the critique. Back at the cabin, Hazel lit the stove, hung her coat, and brewed a fresh pot of tea with a seriousness usually reserved for medical procedures.

She sat at the heavy table carved by her grandfather’s hands. The letter and photograph spread like artifacts of an archaeological dig she hadn’t volunteered for. Her great aunt Clementine, the mysterious mountain woman her father used to mutter about after two glasses of cider, the one who ran away and never came back.

Except apparently she had just not in the polite, well-annannounced way. Hazel lifted the photograph again. Clementine was young, smiling, hair braided thick as rope. A dog beside her, sleek, strong, brighteyed. That was the most unsettling part. Not because the dog looked like Juniper, though it did, but because something in its posture was identical, alert, protective, almost amused. “What are you?” Hazel whispered.

Juniper tilted his head, either confused or offended. For the first time in years, Hazel felt restless. Not unhappy, not afraid, just drawn forward, like someone had tugged a ribbon tied around her ribs. She leaned back in her chair and spoke aloud to the empty cabin. I’m going to Alderbridge tomorrow.

It felt wrong to make a big decision without consulting someone, so she consulted the teapot. The teapot offered no strong opinions. Juniper, however, gave a decisive sneeze, which Hazel took as a vote of confidence. Morning came with missed fingers curling around the cabin windows. Hazel packed a rucks sack, traveling coat, small tin of time biscuits, her walking stick, Clementine’s letter, and the photograph.

She also packed a rope she’d once used for tying firewood bundles because no responsible mountain woman traveled without rope. You never knew when life would require knots. The trail down the ridge was long but kind. Birds fluted above and the air smelled of fur needles and cold stone.

Hazel and Juniper walked without hurry. Hazel talked to the mountains as she went. Just idle chatter. You know, she said, “If this is some test of character, I’d prefer a written exam.” At one point, a squirrel leapt across the path and stared at her like a furry highway official. Hazel raised two fingers in salute. I’m a licensed local. Thank you.

By noon, the forest thinned, and the roofs of Alderbridge came into view. The town lay in the valley like a basket of red apples, small, neat, and smuggly picturesque. It had one road, one bakery, one library, and crucially, one seed shop. Hazel stepped through the door of Fernwood Seeds and a bell jingled above her head. The woman behind the counter looked up. She was perhaps in her mid-30s, freckled, wearing a green apron patterned with tiny carrots.

Her hair was curly enough to catch sunlight like copper wire, and she radiated the calm confidence of somebody who could repot a ficus blindfolded. “Afternoon,” she said. “We have winter bulbs and spring starters. Are you looking for anything in particular? Hazel hesitated. The words felt too heavy in her mouth. I’m looking for someone, she finally managed.

Her name is Mera, the woman said, tapping her own chest. That’ be me, Hazel swallowed. I believe you knew my great aunt Clementine. Mera blinked. Once, twice. Oh, she said quietly. You’re one of the emberwoods. She came around the counter, wiped her hands on her apron, and gestured toward a small table near the window. “We should talk,” Mera said. “But first, your dog. Does he like carrot treats? They’re shaped like stars.

Kids buy them and pretend they’re feeding constellations. We’re past.” Juniper’s ears perked up. Hazel blinked. “Yes,” she said. “He’s extremely interested in astronomy.” Meera smiled. “Good. You’ll both need the energy.” Hazel would later reflect that the universe had quite the sense of humor.

The woman, who knew how to listen to trees, also baked carrot-shaped dog biscuits in star molds. But as Meera placed tea on the table and spoke her first quiet words about Clementine Emberwood, Hazel realized this was no coincidence. The mountains were still whispering, and she was finally listening. Hazel had never been a fan of conversations that began with sentences like, “There’s something you should know.

” Those sentences almost always led to things that required stronger tea, sturdier shoes, and emotional preparation. Mera Fernwood, however, spoke that exact sentence within 5 minutes of settling across from Hazel. They sat in the back of her seed shop in a cozy nook that smelled of soil and cedar. Juniper curled beneath Hazel’s chair, nibbling a carrot-shaped biscuit as if evaluating the bakery credentials of Alderbridge.

There was a framed botanical print on the wall labeled taxis brevifogia u tree. Hazel stared at it while Meera poured tea. Because staring at plants was easier than staring at destiny. Your great aunt Clementine, Meera began, wasn’t just a woman who liked plants and mountains. Hazel lifted one eyebrow. That’s already three more attributes than my father ever gave her credit for. Meera smiled faintly.

Clementine was the keeper of the ridge. Hazel blinked. Like a park ranger? No. Meera said like someone who understood the mountains balance, its seasons, its migrations, its agreements. End quote. Hazel resisted the urge to laugh. Agreements. as if the mountain had signed paperwork. But Meera’s gaze carried no irony.

She opened a drawer and placed a bound notebook on the table. The cover was worn leather, edges frayed, the kind of book that could tell a thousand stories if asked nicely. Clementine left this with me. Meera said, “She said the next Emberwood would know when to ask for it.” Hazel stared at the notebook, beused.

“Well, I didn’t ask. I just arrived and blurted her name. So, I suppose I get partial credit. Mera chuckled softly. Close enough. Hazel opened the notebook carefully. Inside were sketches, handdrawn maps of Cloudstep Ridge, markings of Glenns, old logging routes, caves, streams. Some pages were written in neat script, others hastily scrolled.

There were lists of birds, seasonal plant cycles, and strange entries titled things like, “When the wind refuses to turn and the fifth fox that would not leave.” Hazel flipped to a page near the middle. Cash one, waterfall pocket. Cash two, the orchard that isn’t an orchard. Cash three, the singing hollow. Cash four, only when the snow feels warm.

Hazel closed the notebook slowly. So Clementine wasn’t collecting antique silverware, she whispered. No, Mera said. She was storing knowledge and supplies. Not for survival, for continuity. Hazel frowned. Continuity of what? Hiking club membership? Meera leaned closer. Of caretaking. The ridge has character. It needs a steward.

Someone who respects its rhythms and doesn’t force things. Hazel sat back in her chair. expression blank. Is this about compost? Because I’m very good at compost in one. End quote. Meera looked at her like someone who understood the joke but also saw the iceberg beneath it. Clementine told me you were like her. She said, “Someone who listens to mountains instead of talking over them.

” Hazel scoffed softly. I listen to Juniper. Mountains just shout at me when I forget a raincoat. At the sound of his name, Juniper thumped his tail on the floor, proudly endorsing the accuracy of Hazel’s statement. Meera folded her hands.

You don’t need to decide anything today, but if you want to understand, start with cash, too. It’s east of the ridge near the stone terraces. Have you seen a grove of apple trees that look too young to be wild, but too wild to be planted? Hazel paused. She had seen such trees maybe 12 years ago. A place she’d called the orchard that forgot it was an orchard. Mera nodded as if she could read Hazel’s thoughts like a grocery list. Yes, that one.

Hazel rubbed her temples. So these cashaches aren’t gold or jewels. No, Mera said. They’re lessons, tools, clues. Clementine believed the Emberwood Line understands the mountains memory better than Outsiders. Hazel’s voice gentled. So why didn’t she just tell my father? Meera hesitated. And in that pause, Hazel understood. Her father would have paved the ridge if someone promised him better parking.

It had to skip a generation, Mera said carefully. Cloudstep Ridge doesn’t choose by blood. It chooses by respect. Hazel took a deep breath. So if I just ignore it, Mera shrugged gently. Then someone else will try. Maybe someone less gentle, someone with an agenda that isn’t about stewardship. The ridge doesn’t stay unclaimed. Hazel didn’t reply.

Not because she couldn’t, but because there was a strange sensation settling behind her ribs. Not fear, not obligation. Something older and quieter, like a story that had been waiting for its next narrator. Juniper lifted his head as if sensing the shift. Meera poured more tea. You don’t have to rush. Take the weekend. Think visit cash too if you want or don’t.

The mountain will answer regardless. Hazel stood gathering the notebook like a fragile egg. Thank you. Truly, I’ll consider this properly with snacks. Juniper gave Meera a polite lick on the hand. Meera smiled. Hazel stepped back into the sunlight. The trip home was slower than the journey down. Hazel walked in thoughtful silence, letting the valley fade behind her as the ridge pulled her back like a long lost sibling.

Inside her cabin again, she set the notebook on the table beside Clementine’s letter and photograph. It felt like assembling a puzzle she didn’t know the picture of. She boiled water, made tea, added honey, considered pouring the honey directly into her soul instead. Juniper rested at her feet, head on her boot.

Hazel stroked his fur. You know, she murmured. It would be terribly convenient if you just spoke like a person. Maybe once a year. On my birthday, Juniper yawned. Hazel opened Clementine’s notebook to the orchard entry. Beneath a handdrawn map was a note in ink so faded it looked like a memory. The trees don’t grow fruit for everyone. Hazel exhaled.

Well, she said, I suppose we’re going applepicking. Juniper barked once sharp, eager, definitive. Hazel stood, tied her hair back, and packed rope, biscuits, gloves, and binoculars. Her reflection in the window looked absurdly determined. The mountain was calling, and she was finally answering. Hazel had always claimed she was not an adventurous woman.

She liked routines, familiar paths, and teapotss that whistled exactly when they should. And yet, 2 days after meeting Mera Fernwood, Hazel found herself doing something wildly unreasonable. Hiking toward an orchard that technically shouldn’t exist. Juniper trotted ahead, confident as ever, as if to say, “Don’t worry. I’ve been vetting this orchard for years.” Hazel was not comforted.

The trail was faint, barely a suggestion between stones and roots. Sunlight wo through the branches in threads of gold. Moss clung to rocks like gossip, whispering about secrets only trees could keep. After an hour, Hazel saw them rows of apple trees growing in the kind of deliberate pattern that no forest would design. The trunks were thick and dark. Bark creased like laughter lines.

But there was something else. They were in bloom. It was too early in the season for them to be in bloom. Hazel blinked. Ah, she said, I see the orchard has chosen to ignore the calendar. Juniper circled the nearest tree, tail swishing. Hazel followed, gloved hands brushing petals that seemed unnaturally delicate. She remembered Clementine’s notebook.

The trees don’t grow fruit for everyone. Well, Hazel muttered, hopefully they don’t throw fruit at everyone either. I didn’t bring a helmet. She approached the central clearing. There, between the trees, a stone terrace rose from the earth, ancient and moss kissed. The flat surface bore something unmistakable. A wooden chest, weathered but intact, with a metal clasp shaped like a leaf.

Hazel inhaled, cash too, her palms warmed where the gloves met them. She knelt and lifted the lid. Inside lay no riches, unless one considered riches to be gentle, practical, quietly brilliant gifts. There were canvas seed packets labeled in Clementine script, apple cultivars, mountain squash, wildflower restoratives.

There was a folded woolen blanket, a carved walking stick with ridges worn smooth, and a leather pouch tied with jude string. Hazel untied it. Inside were small, irregular stones, each painted with a tiny symbol. A gust of wind pressed her hair against her cheek, and she felt the mountain lean closer, as if listening.

Each stone bore one image. A fox tail, a raindrop, a spiral, a star, a flower. But one stone was different, etched with a canine paw print. Juniper nudged her elbow gently. Hazel laughed under her breath. Yes, I see it. You’re very clever. No need to brag. Under the stones rested a note. These are guides, not commands. The ridge changes.

The keeper must learn which paths to open and which to leave wild. Hazel traced the ink with one finger. It was Clementine’s handwriting again, looped, steady, completely confident. But what unsettled Hazel most wasn’t the words. It was the smell. A familiar spice, peppermint, and pine. The scent of Clementine’s garden shed when Hazel was a child.

a place filled with tools, apple cores, and one aging marmalade cat who judged visitors with intense moral clarity. Hazel closed the chest gently. “What now?” she murmured. Juniper padded toward the terrace edge. Hazel followed and found something she hadn’t noticed from a distance. A stone marker, not tall, just wide enough for two hands.

On it was carved a simple phrase, “For the next emberwood, when the fruit comes.” Hazel tilted her head. When the fruit comes, what am I meant to do? Sing to the trees? She looked up at a branch. A single apple hung above her, just one glowing like polished amber. Hazel reached up. The apple detached with no resistance, as though it had been waiting. She bit into it. It tasted like childhood summers.

She barely remembered. Crisp, bright, and impossibly sweet. Her eyes welled. Juniper leaned against her leg. Hazel laughed softly. Oh, all right, she whispered to the ridge. I’ll keep your secrets, but you had better stop being dramatic. The mountains real work. Spring flowed into summer like warm honey.

Hazel didn’t become an official keeper of the ridge because the mountain didn’t issue certificates or badges. What she became instead was something quieter, watcher, listener, gardener of odd places. She planted clementine seeds near her cabin. The squash vines grew thick and stubborn. Wild flowers sprang up in joyful chaos. Birds tried to steal things. Hazel scolded them and they ignored her. It was deeply therapeutic.

People from Alderbridge sometimes climbed the trail lost hikers, curious teenagers, the occasional botist. Hazel greeted them with tea and mild sarcasm. She taught them which firewood smoked too much and which mushrooms to leave alone. She didn’t tell them about the caches. Some knowledge had to wait for its rightful ears.

The orchard became her second sanctuary. When she visited, the blooms always greeted her, even out of season. Juniper sat beneath the trees as if standing guard. Hazel began to suspect that the dogs of her family were not entirely ordinary. And then on a summer afternoon so warm that even the beetles seemed sleepy, Hazel returned to the orchard and found something she had not expected.

Another apple waiting for her. Not for a visitor. Not for a thief. Not for a town councilman with ecoourism ideas. For her. Hazel tilted her head toward the nearest tree. Fine, she said. I’ll take the hint. We’re in this together. The wind brushed her cheek like approval. A visit at last. Meera visited one day in late autumn, bringing cinnamon bread and a small journal. Hazel fed her tea and biscuits.

Juniper sprawled in the doorway like a living rug. Meera looked around the cabin, eyes soft. You’re settling in. Hazel smirked. I’ve been here 22 years. I’m not exactly a nomad. No, Mera said gently. I mean here, she tapped her chest. With your calling. Hazel blinked. Calling, she repeated.

You make it sound like I’m running a secret mountain clubhouse. Meera didn’t deny it. Hazel brought the walking stick from Cash, too, and rested her palm at top it. I don’t know if I’m doing it right, she admitted. You’re doing it, Mera answered. That’s how Clementine started, too. Hazel laughed. The kind of laugh that sounded like wind rustling through pine.

Well, she said, “Maybe she’ll send a sign if I’m about to ruin everything.” Seasoned Jastine. Juniper barked once. Meera grinned. She already did. She sent Juniper. Hazel rolled her eyes, but her heart warmed. The keeper emerges. Winter dusted cloudstep ridge in white.

Hazel hung lanterns along the path for lost travelers, and recipients of her kindness repaid her with jars of jam and gossip. She pretended not to enjoy the gossip, but she took notes anyway. She found cash 3 in spring, the singing hollow, and left it undisturbed, except for one linen bag of seeds. Cash 4, she sensed, would wait until snow felt warm again. The mountain was patient. She could be, too.

Sometimes Hazel stood outside and felt the ridge breathing beneath her boots. She thought of Clementine, her fierce eyes, her careful handwriting, her refusal to abandon responsibilities simply because no one understood them. Hazel finally understood. Caretaking didn’t make headlines. It didn’t involve medals or applause.

It was quiet service that outlived generations. Hazel knelt beside Juniper one evening and scratched behind his ears. “You know,” she murmured. “I thought I came here to retire.” Juniper licked her hand. Hazel smiled. But I suppose I came here to begin. Epilogue the ridge remembers. Years later, the people of Alderbridge no longer spoke of Cloudstep Ridge with the same timid awe they once had.

They spoke of it fondly, like an eccentric aunt who kept unusual hobbies, and occasionally mailed you jams in jars without labels. If travelers asked why the paths were always clear, why the orchard bloomed out of season, or why lost hikers never stayed lost for long, locals only shrugged and said, “Oh, that’s just Hazel.” Hi, NP.

Hazel Emberwood was no longer the woman who lives up there with the dog. She had quietly and entirely unintentionally become something more, a teacher, a listener, a gardener of good stories. She never announced her position as keeper of the ridge because she didn’t see it as a title, only a relationship. The mountain looked after her, and she looked after it. Simple as that.

Juniper grew older, too, in that calm, wise way some dogs do his muzzle silvering, his eyes still bright gold. He moved more slowly in winter. But when Hazel opened the door at dawn, he still pressed his nose to the wind as if asking what the ridge needed today. Hazel would say things like, “Tell me if anyone’s fallen into the creek again.

” Or, “If a deer is eating my squash, at least ask it to write a thank you note.” And Juniper, patient, polite, uncomplaining, would go, “He always returned, always in his own time. Sometimes a curious visitor would hike the ridge and find Hazel pruning wild flowers or rearranging stones with the seriousness of an architect.

They would offer to help and Hazel would simply hand them gloves as if she had been waiting for them all along. Most stayed for tea. Some stayed long enough to learn which clouds meant rain and which meant don’t bother hanging laundry. A few, on rare occasions, felt the ridge whisper to them. Hazel never forced lessons.

Knowledge was offered, never pushed, like apples that ripened when they pleased. Every now and then, she’d visit the waterfall cave or the orchard terrace and speak softly to the moss or the wind. Not because she expected an answer she wasn’t unreasonable, but because she’d learned something about secrets. Secrets aren’t meant to be hoarded.

They’re meant to be tended, grown with care, passed on at the right moment. And one evening when the sun melted behind the ridge in colors so warm they turned the trees to copper. Hazel sat on the cabin steps. Juniper’s head in her lap. She smiled at the horizon and said, “I suppose I understand now why you left it to me, Clementine. You didn’t want someone to guard the mountain.

You wanted someone to love it.” The wind rustled the pines in reply, as if saying, “Yes.” In the end, Hazel Emberwood didn’t change the mountain. The mountain changed her. If you enjoyed this story, click the video on your screen now to watch another unforgettable tale where destiny and courage collide in ways you never expected.

Don’t forget to subscribe and consider to hype our video to help us keep bringing you more stories like these. Your support means everything to