In Batanes, the Philippines’ northernmost island, Indigenous peoples’ farming practices serve as a model for food sovereignty and climate resilience.

Women farmers cultivate land during a Payuhuan at Imnajbu, Batanes. Payuhuan is a communal gathering where farmers collectively prepare the land for free, with the harvest proceeds divided among participating members of their farming cooperative. This practice is common among the Ivatan, who traditionally support one another in farm work without expecting payment. 29 Oct., 2022.

Marilou Fitero and her then 6-year-old daughter, Dianne, were huddled under their table for hours, their hands pressed tightly against their ears to block out the deafening roar of 215 kph winds and the terrifying sound of iron sheets being torn from roofs and hurled across their hometown.

Batanes is the smallest island-province in the Philippines, located at the northernmost tip of the archipelago. This isolated island, positioned within the Pacific’s typhoon belt, is home to over 18,000 indigenous Ivatan people, who are renowned for their resilience in the face of severe storms.

But Kiko, a super typhoon in the region, was one of the most devastating storms the island had ever experienced.

Marilou Fitero’s daughter points out water leaks inside their home. 3 Nov., 2022.

There was no water or electricity for a month. People had to collect potable water from various locations during the aftermath. Fitero suffered a fracture on her right arm when their roof collapsed onto her, and for her daughter Dianne, who loved watching television, the storm took away her favorite pastime.

Such weather disturbances are not uncommon in a country that faces around 20 typhoons annually, which have become progressively more destructive due to climate change. A 2019 report by the Institute for Economics and Peace declared the Philippines as the country most at risk from the climate crisis.

Senior scientist Dr Rodel Lasco describes typhoons in simpler terms: “they are a weather phenomenon with very strong winds, which disrupts like a hurricane and is accompanied with a strong rainfall.”

Dr Lasco is the executive director of The Oscar M. Lopez Center, a Pasig City-based foundation that harnesses science to build climate resilience for vulnerable populations.

Sudden downpour in Imnajbu, Batanes, disrupts a farming day. 29 Oct., 2022.

According to Lasco, models indicate a trend toward fewer typhoons, but those that do occur are expected to be stronger or more intense with each event. “Even one strong event could wreak havoc on communities,” Dr Lasco told FairPlanet.

One of the main livelihoods on the island is farming, and several Ivatan farmers, like Fitero, have noticed a similar trend in Batanes.

While theoretical discussions on climate change have barely entered mainstream conversations, the Ivatan – who integrate indigenous knowledge and science into their farming practices – have observed that fewer but stronger typhoons are making their seasonal farming calendar less predictable and harder to follow.

For a community whose livelihood heavily relies on tourism, combined with a culture and lifestyle deeply rooted in agriculture, the climate crisis poses a significant threat to both their jobs and food security.

‘FARMING IS SYNONYMOUS WITH SURVIVAL’

Magdalena Fabre at her farm in Mahatao, Batanes. 6 Aug., 2022.

Magdalena Fabre, a 72-year-old farmer, could barely remember how old she was when she first began accompanying her parents to their farm in Mahatao, Batanes. Farming was so deeply intertwined with her childhood that she can’t recall the first time her fingers touched the soil.

“As a child, my parents would ask me to bring their tools to our farm, and that’s how I learned little by little. I had to help my parents on the farm because farming was synonymous with survival,” Fabre told FairPlanet.

Fabre was the oldest daughter in a family of 11. Like many in her generation, her family planted crops primarily for sustenance. Given that Batanes is frequently hit by typhoons, root crops such as uvi (yam) and wakay (sweet potato) were ideal choices for planting.

These crops grow underground, making them less vulnerable to strong winds and rain in comparison to soft rice grains, which grow above ground.

Uvi and wakay are typically steamed and eaten with a viand. They are rich in fiber, potassium and antioxidants, making them beneficial for improving blood sugar control – as opposed to white rice, which is commonly eaten in the Philippines and has been linked to an increased risk of diabetes.

On the mainland, these root crops are often transformed into sweet delicacies.

“We only harvest what we need for the day, and since there were no markets before, we barter excess vegetables to other households who have what we need,” recalled Fabre.

Fabre harvesting wakay at her farm in Mahatao, Batanes. 6 Aug., 2022.

Anthropologist Dr Maria Helen Dayo, who has conducted several studies on farming and gender in Batanes, noted that the Ivatan people’s planting practice reflects their approach to food sustainability.

“They do staggered harvesting according to needs. Some of the food that they harvest are also kept in small granaries or are left on top of the soil and covered with leaves until they need it again to plant,” Dayo told FairPlanet.

Food production was also sustained by rotating root crops, with farmers planting either Uvi or Wakay depending on what was available.

According to ‘Stories of Adaptation to Climate Change,’ a book published by the Philippine Department of Agriculture and Bureau of Agricultural Research (DA-BAR) and the University of the Philippines Los Banos-College of Agriculture and Food Science (UPLB-CAFS), most Ivatan practice a root crop-based cropping system in response to the climate variability in the province.

Ivatan farmers also allow their parcels of land to rest every two to three years to maintain the soil’s natural fertility. During this period, the land is used for cattle grazing while the soil regenerates.

For Fabre and many other Ivatan farmers, farming is traditionally organic or naturally grown because they prefer eating organic produce. They also avoid chemical fertilisers due to their long-term negative impacts on the soil.

A portrait of Fabre at her farm in Mahatao, Batanes. 9 Feb., 2023.

Dayo commends this farming culture for its elements of sustainability. She believes that if nurtured, this approach could position Batanes as a viable model for food sovereignty – a framework essential for combating food insecurity, especially in the face of the climate crisis.

In “Food Sovereignty: A New Rights Framework for Food and Nature?,” a journal article written by Hannah Wittman, The Nyéléni Forum for Food Sovereignty defines food sovereignty as: “The right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their food and agriculture systems.

It further reads, “Food sovereignty prioritises local and national economies and markets and empowers peasant and family farmer-driven agriculture, artisanal fishing, pastoralist-led grazing, and food production, distribution, and consumption based on environmental, social, and economic sustainability.”

Fabre plants Uvi with her family, while teaching some teenagers to farm. 9 Feb., 2023.

Fabre plants Uvi with her family, while teaching some teenagers to farm. 9 Feb., 2023.

However, while many elders continue to practice sustainable natural farming, this lifestyle is not as familiar to the present generation, who have shifted to more “stable” forms of livelihood, such as tourism.

REVIVING THE “PAYUHUAN”

Dianne plays with preserved taro stalks, which can last for years. The traditional Ivatan viand “vunes” is made by mincing these stalks and mixing them with pork. 8 Aug., 2022.

Dianne plays with preserved taro stalks, which can last for years. The traditional Ivatan viand “vunes” is made by mincing these stalks and mixing them with pork. 8 Aug., 2022.

Evangeline Nanud, an elderly agriculture elementary school teacher in the municipality of Uyugan, shared that children today find it difficult to farm because, unlike her generation, the present generation did not grow up in the fields.

“Now, the younger generation barely knows how to hold an Ishwan (hand bar). Their hands only hold cellphones,” she said jokingly.

Nanud teaches vegetable farming to Grade 5 students. In her class, students are grouped to plant, harvest and cook vegetables like eggplants, talinum and cabbage. She observed that the younger generation, having grown up eating processed foods, only begins to appreciate vegetables and farming later on.

During the peak of tourism, households experienced food scarcity as they couldn’t buy vegetables from farmers who prioritised selling to higher-paying tourist establishments.

“Kids need to develop their love for farming because our future is uncertain,” she added.

“You will not experience hunger if you plant,” reads a sign at an elementary school garden in Uyugan, Batanes. 2 Aug., 2022.

Starting 2020, during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, and throughout the country’s nearly three-year lockdown, tourist arrivals on the island drastically plummeted to a total of 10,000, according to a private data sheet shared with FairPlanet by the Philippine Statistics Authority. This decline led to a renewed focus on what has always been essential to the island: farming.

“Elders considered farming as odd work since farming is difficult. They would tell us to study hard in school so that we won’t work under the heat,” recalled Delfin.

However, he later realised that in an island province like theirs, farming is essential and must continue.

Indigenous seeds kept by Fabre: Puhug (winged bean), Agayap (Beans) and Tavayay (Bottle Gourd).

“Farming should never be [abandoned] as an occupation for us Ivatans, because our lives as indigenous peoples are anchored to our land. Our land is our life, and our resiliency and survival depend on it,” said Delfin.

During the lockdown, quarantine regulations prevented the tightly bonded community from seeing each other, so they turned to farming together. It was one of the few community activities allowed since it was categorised as “essential work.”

Farmers share a meal while resting after a morning of Payuhuan. Gin is a common drink among the Ivatan, providing warmth during these communal gatherings. 29 Oct., 2022.

Delfin emphasised the importance of keeping their communities together, stating that even with the advent of modern technologies, it is still the people who are responsible for helping one another.

This building, once a restaurant in Sabtang, Batanes, was ravaged by Typhoon Kiko. Since it is made of durable stones, the structure remained intact despite the storm’s destruction. 10 Aug., 2022.

While Typhoon Kiko destroyed infrastructure, there were zero casualties in Batanes, which many believe is due to their strong sense of community and organisation.

In the capital, Dr Lasco remains optimistic about the future generation.

“The Ivatan have been hit by strong typhoons, winds and rains. Their existence is a community adaptation we could learn from,” he said.

A CLIMATE-RESILIENT HOME

Dianne celebrates her 7th birthday at home with her friends. 28 Oct., 2022.

Back in Fitero’s home, still bearing the damage from Typhoon Kiko, Dianne celebrated her 7th birthday. On the dining table, there was a mix of Ivatan staples and influences from the capital. Yet, the essence of Ivatan culture remained.

The elders came together to harvest and cook uvi, wakay and turmeric rice, while the children enjoyed small portions of the traditional dishes.

Fitero and her daughter Dianne after a farm day in Basco, Batanes. 6 Feb., 2023.

The next day, Fitero returned to her small plot of land to farm. She shared that she had worked for years in Manila, but returned to farming on the island as it became a practical choice for a mother caring closely for her growing daughter.

However, life isn’t exactly easier – when it rains, she and Dianne pull out rugs to wipe away the water leaks from their iron roof. And because saving as a farmer is difficult, buying the cement needed to repair their roof will have to wait.

Dianne playing with rocks at the beach. 7 Feb., 2023.

After spending weeks with the author, Dianne expressed her dream of becoming a photographer. She hopes to save enough money to build a traditional Ivatan stone house in the future so that their roof “won’t flee” when typhoons as powerful as Kiko ravage their home again.

News

SHOCK at close-up rescue operations in Philippines following landslide triggered by Storm Yagi

Search and rescue operations continue in Antipolo, Rizal, at the site where people may be buried following a landslide triggered by Tropical Storm Yagi (Anadolu via Getty Images) Search and rescue operations continue in Antipolo, Rizal, at the site where…

HOT:Super Typhoon Yagi kills four in Vietnam after casualties in China and Philippines

Summary Yagi is Asia’s most powerful storm this year Winds reach up to 160 kph as Yagi approached Vietnam Death toll stands at 22 people HANOI/HAIPHONG, Sept 7 (Reuters) – Asia’s most powerful storm this year made landfall in northern…

FACT CHECK: No expected tropical cyclone bigger than the Philippines

FACT CHECK: No expected tropical cyclone bigger than the Philippines The potential weather disturbances that have a ‘high probability’ of developing into tropical cyclones in the next two weeks have yet to have intensities determined Claim: According to a Facebook post,…

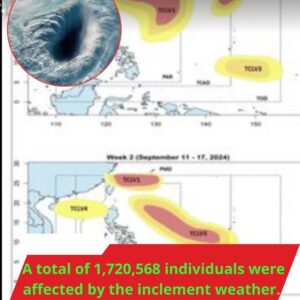

PAGASA warns of three tropical cyclone -like threat for the next 2 weeks

This photo shows Coast Guard personnel rescuing residents in Northern Samar during the onslaught of Severe Tropical Storm Enteng (international name: Yagi). Released / Philippine Coast Guard MANILA, Philippines — After Severe Tropical Storm Enteng (international name: Yagi), several tropical cyclones…

The truth about the super large storm about to appear near the East Sea

Rumors of a super typhoon forming near the East Sea, larger than the area of the Philippines, are spreading on social media. Rappler’s latest typhoon report says that according to a Facebook post, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services…

(Video)Close-up of the aftermath in the first place affected by Typhoon Yagi.

The scene was extremely chaotic and severely damaged after the storm. There was great loss of life and property. According to initial statistics from experts, the estimated damage was up to 6 million USD and is at risk of increasing….

End of content

No more pages to load