A white German Shepherd puppy, maybe just a teenager, was trapped in the nets and couldn’t get out of the water. It was truly a scene that broke my heart. But what shattered me even more is what you’re about to learn later in this story. You will be shocked just as I can never forget it.

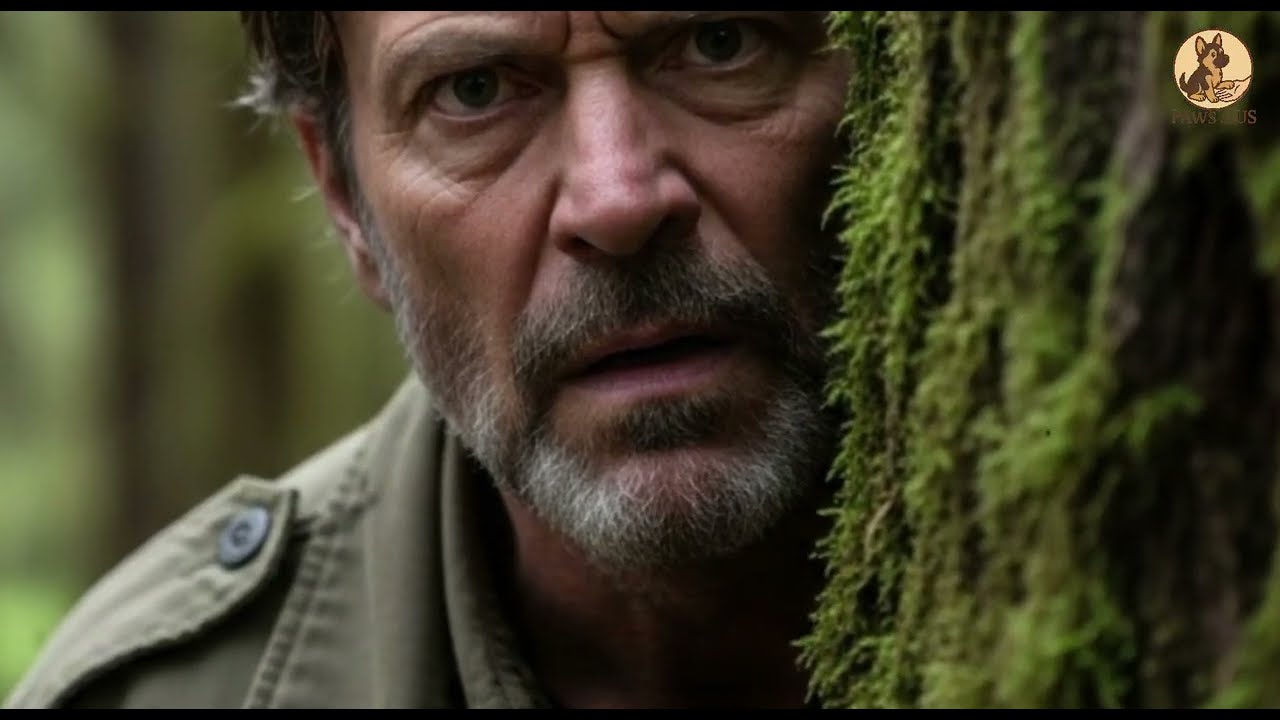

My name is Elias Vance, but nobody’s called me that in a long time. It’s just Eli. I’m 50 years old and my world has shrunk to the size of 10 acres of dense Oregon forest and the quarter mile of the Elca River that borders it. It’s a small kingdom, but it’s mine. The army paid for it with a monthly disability check and my left arm, which I left behind in the dust and chaos of Fallujah.

It was a trade I’d make again. The quiet I found here is worth more than any limb. The quiet isn’t silence. Silence is what you get in a holding cell or a tomb. My quiet is a symphony. It’s the percussive tap of a woodpecker on an old growth cedar, the soprano cry of an osprey circling high above, and the constant bassopruno rush of the river over a bed of ancient smooth stones.

It’s a living sound that fills the empty spaces inside me. The ones carved out by the shriek of incoming mortars and the shouting of young men who would never get old. My days are built on routine. Routine is the scaffolding that keeps a man like me from collapsing. I wake before the sun when the air is still thick with mist and smells of damp earth and pine.

I make coffee on the stovetop, the old-fashioned percolator hissing and bubbling, a rhythm that starts my day. I sit on my porch, a mug warming my one good hand, and watch the world wake up. I see the light creep over the ridge, turning the river from pewtor to jade. I watch the deer come down to drink, cautious and graceful. This is my church. This is my therapy.

After coffee, I walk. It’s not a stroll, it’s a patrol, a perimeter check. Old habits die hard. I walk the same path every day. My boots knowing the way, my eyes scanning the treeine. I know every fallen log, every game trail, every patch of ferns.

It’s a ritual that grounds me, that reminds me that for all the world’s madness, the seasons still turn. The river still flows and the sun still rises. It’s a promise of permanence in a life that taught me nothing is permanent. That particular morning in late autumn began no differently. The air had a crystallin sharpness to it, a promise of the winter to come.

The leaves on the vine maples had turned a brilliant, defiant crimson in gold, and a few had begun to let go, drifting down to carpet the forest floor. I had my right hand shoved deep in the pocket of my worn field jacket, the empty left sleeve pinned neatly to the shoulder, a silent testament to a life lived before this one.

I was halfway through my patrol, thinking about the integrity of a retaining wall I’d built and the cord of wood that still needed splitting when a sound intruded upon my quiet. Laughter. It wasn’t the warm communal sound of people sharing a moment of joy. This was different.

It was sharp and jagged, full of a strange aggressive energy that didn’t belong here. It was the sound of mockery. It sliced through the morning’s piece like a shard of glass. I stopped, my headcocked, listening. The sound was drifting up from a small pebbled inlet about 100 yards downstream, a place where the main current eddied and slowed.

My first instinct, born from years of self-preservation, was to ignore it. My fighting days were over. I’d earned my peace by learning to turn my back on the world’s ugliness. It was probably just some city folks out for the weekend being loud and careless. It was not my business.

I’d spent too many years making other people’s business my own, and it had cost me dearly. I took a few more steps, trying to push the sound away, to let the river’s songs swallow it. But another peel of laughter rose, louder this time, followed by a voice. The words were indistinct, but the tone was clear. It was the sound of taunting. Against my better judgment, I veered off my path.

I moved through the dense undergrowth of salal and sword ferns, my boots making no sound on the damp, mossy ground. The soldier in me took over, placing each foot with care, using the massive trunks of the Douglas furs for cover. I was just going to take a look, satisfied the nagging feeling in my gut that something was wrong, and then go on my way.

When I reached a vantage point, peering through a curtain of hanging moss, the scene below snapped into focus, and the knot of unease in my stomach tightened into a cold, hard lump of ice. There were two of them, men, not boys, though they had the careless cruelty of teenagers. They were probably in their late 20s, dressed in brand new, expensive looking waiters and fishing vests that were conspicuously clean and empty.

They looked like they’d stepped out of a catalog, playing a part rather than living a life. And between them, they had a puppy. It was a tiny thing, a ball of pure white fluff with ears too big for its head and clumsy paws. A husky mix maybe, or a shepherd. It couldn’t have been more than eight or nine weeks old.

One of the men, a thick-necked individual with a smug grin, was holding it by the scruff of its neck. The puppy was squirming, its little legs paddling frantically in the air, letting out a series of high-pitched, terrified yelps that were being swallowed by the men’s laughter.

My one hand, deep in my pocket, clenched into a fist so tight the knuckles achd. The quiet symphony of my morning was shattered, replaced by a roaring in my ears. The second man, taller and thinner with a phone in his hand, was speaking. “You sure about this, Caleb? It seems like a lot of trouble.” “Relax,” Caleb grunted, giving the puppy a rough shake.

“This is how you make him tough. It’s a water dog, right? Supposed to be. We’ll give it a little test. Sink or swim. Builds character.” He said it with such casual disregard, as if he were talking about tossing a stick. The other man laughed, a nervous, uncertain sound, and then reached into a canvas bag.

He pulled out a disgusting tangled mess of old fishing net. It was dark green and stiff with dried algae. Knotted into one end with a length of frayed rope was a smooth gray riverstone bigger than my fist. It was a weight, an anchor. My breath caught in my throat. This wasn’t a test. This wasn’t training. This was something monstrous. This was a slow, deliberate execution disguised as a joke.

They wrestled the puppy, their movements rough and impatient. The little creature cried out, a sound of pure, unadulterated terror that lanced through the peaceful air and straight into my heart. It was the sound of the utterly helpless, the sound of innocence meeting inexplicable malice.

It was something I had traveled halfway around the world and lost a part of myself to fight against. They managed to wrap the net around the puppy’s small, struggling body. It was a clumsy, brutal affair. One of its front legs was hopelessly caught in the mesh, twisted at an unnatural angle. The net cinched tight around its chest, a crude, deadly harness.

Caleb held the weighted netted puppy up. The little creature had stopped yelping and was now trembling violently, a low prier escaping its throat. “Ready to get your character built, little dude?” Caleb sneered. He began to swing the puppy back and forth like a pendulum.

“Just get it over with,” the other one said, raising his phone as if to record the event. “Here we go!” Caleb shouted. And with a final powerful underhand swing, he launched the puppy out over the water. The small white body sailed in a pathetic arc and hit the surface with a splash that seemed shockingly loud in the sudden silence. For a hearttoppping second, there was nothing but ripples spreading across the jade green water.

Then a frantic churning began just below the surface. A froth of bubbles erupted as the puppy’s instinct screamed for survival. But the weight of the rock was merciless. It did its job instantly, pulling the net and the puppy trapped within it down, down, down toward the dark riverbed.

I could see its ghostly white form struggling, a desperate, panicked dance against the inevitable. On the shore, the two men exploded with laughter. It was a hollow, ugly, gutless sound that desecrated the morning. “Whoa, look at it fight!” Caleb howled, slapping his thigh. “Told you’d add some spirit.

” “It won’t for long,” the other one said, his voice laced with a sick amusement. “That current’s strong. It’ll get tangled in the rocks.” Then Caleb said the words that broke the last thread of restraint within me. He looked at his friend, a wide, cruel grin splitting his face. “Let it drown,” he commanded, as if he were a god passing judgment. Let us see how long it takes. That was it. The world went silent.

The river, the birds, the wind, it all faded away. A switch flipped inside my head. A switch I hadn’t touched in 10 years. The quiet man of the woods, the peaceful veteran seeking solitude was gone. In its place stood Sergeant Vance. And Sergeant Vance had a new mission. There was no thought. There was only action.

In combat, you learn that hesitation is a killer. You assess, you decide, and you execute. I burst from the cover of the trees, shrugging off my heavy jacket as I ran. I didn’t shout a warning. I didn’t waste breath on threats. Wasting breath on them would be wasting seconds the puppy didn’t have.

Their heads whipped in my direction, their laughing faces instantly contorting into masks of confusion. Then alarm. I paid them no mind. They were irrelevant. My eyes were locked on the roing patch of water where the puppy had gone down. The Alia River in late autumn is more than just cold. It’s a living, breathing entity of ice. The mountain chill seeps into it, turning it into a liquid cryosshock.

It’s the kind of cold that doesn’t just numb you, it attacks you. It feels like a thousand sharp needles piercing your skin, stealing your breath, and squeezing your heart in a vice. I didn’t slow down. I hit the water’s edge and launched myself into a shallow running dive. The shock was absolute and overwhelming. It was a physical assault.

The cold was so intense it felt like fire, a searing electric pain that shot up my legs and into the marrow of my bones. For a split second that stretched into an eternity, every muscle in my body seized. The air was driven from my lungs in a silent, involuntary explosion. My mind screamed one primal word, out. But my training screamed louder. Control your breathing.

Don’t panic. Panic is a luxury. Panic gets you killed. I forced down the instinct to gasp for air, knowing that a single lung full of that icy water would be the end. I forced my muscles to unlock, to obey. I opened my eyes underwater. The world dissolved into a blurry, disorienting chaos of green and brown.

Particulate matter stirred up from the bottom drifted past my face like malevolent spirits. The sunlight from above was a diffuse, hazy glow, a distant and unreachable heaven. The current, far stronger than it looked from the bank immediately began to tug at me, trying to drag me downstream away from my target. I kicked hard, my legs already feeling like lead.

I drove forward with my one good arm, pulling myself down deeper into the chilling gloom. Where is it? Where is that flash of white? My lungs were already beginning to burn. The familiar fire of oxygen deprivation starting its slow, insistent creep. I scanned the riverbed, a bleak alien landscape of smooth algae slick stones, rotting leaves, and thick layers of silt. Then I saw it.

a flicker of movement, a patch of white against the dark bottom. The puppy was about 10 feet down, its small body pinned to the riverbed by the weight of the rock. It was still fighting, but the movements were becoming weaker, more sporadic. A small, pathetic cloud of silt was being kicked up by its back legs.

A silent, desperate scream against the dying of the light. Its front paw was horribly twisted in the mesh, and the main body of the net was cinched so tight around its chest that it could barely move. Every twitch of its body only served to wedge it more firmly among the rocks. Three powerful kicks brought me to it.

The pressure was building in my ears. A dull, throbbing pain. I reached out and grabbed the coarse netting. My first desperate instinct was to simply tear it open, to rip the puppy free through sheer force. But the netting was thick, commercial-grade nylon, and with only one hand, it was like trying to tear a phone book in half.

My fingers, already stiff and clumsy from the numbing cold, fumbled uselessly with the knots that held the net together. They were swollen and tight, unforgiving. A stream of precious air bubbles escaped my lips against my will. My body was betraying me, screaming for a release I couldn’t give it.

The fire in my chest was intensifying, growing from a campfire to a roaring inferno. Not yet. Hold on, just a little longer. I looked at the puppy. Its eyes were open. They were wide with a terror so profound, so absolute that it seemed to vibrate in the water around us. It was the look of someone who knows the end has come. A silent plea that transcends species.

A question I had seen in the eyes of dying men. Why is this happening? In that moment, under 10 ft of freezing water, it wasn’t just a dog. It was a life, a small, innocent, fighting life being extinguished for the amusement of monsters. No, not today. Not on my watch.

The old creed, the promise we made to each other in the sand and the dust, echoed in the deepest part of my mind. Leave no one behind. It didn’t matter if they had two legs or four. Rage is an incredible fuel. It can burn hotter and brighter than fear. A cold, clear rage filled me, burning away the panic, sharpening my focus. The knots were a dead end. I followed the netting to its source, the heavy stone.

The rope was tied with a series of simple but brutally effective hitches. My numb fingers, which felt like wooden dowels than parts of my own body, scrabbled at the wet, swollen rope. I pulled. I twisted. I tried to jam my thumbnail between the fibers to gain some purchase. It was useless. The knot was set. My vision began to swim. Black spots danced at the edges like flies.

My lungs felt like they were on the verge of rupturing. This was the moment of decision, the point of no return. I had a choice. I could push off the bottom, kick for the surface, and save myself. Or I could stay here and die with this dog, another casualty in a meaningless war.

The image of those two laughing faces on the shore flashed in my mind. The thought of them walking away, of them winning, of this little life being erased for their sick entertainment, it was unacceptable. I braced my boots on the rocky riverbed for leverage. I grabbed the section of net just above the rock with my one hand, wrapping it around my wrist, and I pulled.

I put everything I had left into that single desperate act of will, the strength in my back and legs, the fury in my soul, the weight of every ghost I carried. For a second that seemed to last an hour, nothing happened. The rope cut deep into the flesh of my palm, but I didn’t feel the pain. I just held on, roaring, a silent scream into the water and pulled. Something gave. It wasn’t the knot.

It wasn’t the rope. It was the net itself. An older, frayed section near the rock, weakened by time and decay, tore open with a dull, submerged, ripping sound. It wasn’t a clean break, but it created a large enough hole. The net was no longer anchored. I didn’t waste a microcond.

I shoved my arm through the tear, scooping up the puppy’s small, cold body, bundling the tangled net and the little creature against my chest. He was frighteningly limp. I kicked off the bottom with every last ounce of strength I possessed. The ascent was an agonizingly slow motion journey back to the world of the living.

The oppressive green water slowly, grudgingly lightened to a pale, hopeful gold. The pressure in my head was immense. A crushing weight that threatened to make me black out just a little more. Kick. Kick. My head broke the surface. The sound I made was not human. It was a raw, ragged, desperate gasp for air. It was the most beautiful, most painful, most glorious breath I have ever taken.

It tasted of life. I coughed violently, sputtering river water. My entire body convulsing with a violent, uncontrollable shivering. I looked down at the bundle clutched in my arm. The puppy was limp, motionless, his head still submerged. “No, no, you don’t,” I rasp, my voice a raw croak. “You don’t quit now.

” I shifted my grip, a clumsy maneuver with my numb hand, and lifted his small head above the water. His eyes were closed. His body was a dead weight. He wasn’t breathing. A fear colder and sharper than the river itself lanced through me. I had been too slow. I had failed.

“No,” I growled and began to fight my way toward the shore. The effort was monumental. My limbs were heavy, unresponsive logs. The cold had stolen all my strength, and the adrenaline was starting to fade, leaving behind a deep, aching exhaustion. Each kick was a battle against the current and my own failing body. When my feet finally scraped against the muddy bottom, I stumbled, falling to one knee in the shallows.

I cradled the puppy in my lap, my heart hammering a frantic, desperate rhythm against my ribs. Come on, kid. Come on, breathe. I whispered, my teeth chattering so hard I could barely form the words. I scrambled onto the pebbled shore, and gently laid him down. I remembered a field first aid course I’d taken decades ago, one that included a brief section on animals.

It had seemed like a waste of time then. Now it was a prayer. On pure instinct, I tipped him upside down, his head hanging low, and gently but firmly squeezed his chest. A sickening stream of river water poured from his mouth and nose. I laid him back down to his side. Still nothing. No breath, no movement.

I couldn’t give up. I pinched his little muzzle closed, sealed my mouth over his nose, and gave two small, gentle puffs of air. I watched his chest. Did it rise? Maybe a little. I couldn’t be sure. I found the spot on his rib cage just behind his elbow, and began compressions with two fingers.

My own shivering was so violent that it was hard to maintain a rhythm. One and two and three and four. Then another breath. Come on, you little fighter. You didn’t fight that hard down there just to give up. Now you show them you live. I repeated the cycle. Compressions, breath, compressions, breath. The world narrowed to this single desperate task.

The cold, the pain, my own exhaustion, it all faded away. There was only the feel of his small, still ribs under my fingers. On the third cycle, as my lips left his nose, he gave a tiny, convulsive cough. A shudder ran through his whole body. It was a spark.

He coughed again, a wet, or ragged, rattling sound, and then he took a breath. It was a shallow, hitching, pathetic little gasp, but it was breath. His eyes fluttered open for a second, then closed again. He was alive. A wave of relief so powerful it felt like a physical blow washed over me, and I collapsed backward onto the wet gravel. My body was screaming. Every muscle achd.

My joints were on fire from the cold. And I could see now that my hand was bleeding freely from where the netting had cut into it. But I smiled. A real genuine bone deep smile. And that’s when I remembered I wasn’t alone. I slowly pushed myself up, my movement stiff and painful. I looked across the inlet.

The two men were still there, standing at the edge of the woods like a pair of cheap statues. Their laughter was long gone. Their smug expressions had been replaced by a mixture of disbelief and a dawning, ugly looking fear. Their little afternoon of sport had been violently interrupted by a crazy one-armed old man who had without a word launched himself into a freezing river. Their narrative had been hijacked. I got to my feet, swaying for a moment.

I stripped off my soaked thermal shirt and without a second thought wrapped the shivering puppy in its relative warmth. I pulled him close to my chest, trying to share what little body heat I had left. He let out a weak, pitiful whimper and tried to burrow closer. I started walking toward them.

My limp, a souvenir from an IED, was more pronounced than usual. I must have been a hell of a sight. A soaking wet, bleeding, half- naked old man clutching a half-drowned puppy marching toward them with an expression that was anything but friendly. Caleb, the leader, found his voice first. It tried for belligerance, but landed somewhere near a nervous squeak. Hey man, what the hell is your problem? That’s our dog.

I stopped a few feet from them. I didn’t say a word at first. I just looked at them. I let my eyes travel from their clean, expensive boots to their stupid, cruel faces. I let the silence stretch. Let it hang in the cold air. Let them feel the full weight of my stare.

In my old line of work, I learned that a quiet, focused intensity is far more intimidating than shouting. Shouting is for people who have lost control. “This dog,” I finally said, my voice low and raspy, a grally sound torn from a frozen throat. “You mean this animal you just tried to murder for a cheap laugh?” “We weren’t murdering it,” the other one stammered, looking to his friend for backup that wasn’t there.

It was a It was a training exercise to make it tough. A harsh, bitter laugh escaped my lips. It was the most pathetic, cowardly excuse I had ever heard. Tough? I took a deliberate step closer. They both instinctively took a step back. You want to lecture me about what it means to be tough? You who gets his courage from torturing a 9-week old animal? Let me give you a lesson, son.

Tough is not about inflicting pain on something smaller and weaker than you. That’s not strength. That’s the very definition of cowardice. Tough is about standing between the helpless and the harm that’s coming for them. Tough is diving into a river that’s trying its best to kill you, to save a life, not standing on the shore with a phone in your hand, waiting for that life to be extinguished. I adjusted the puppy in my arm.

He pressed his cold, wet nose into my neck, seeking warmth, seeking safety. He knew who his enemy was. “Now, here’s how this is going to go,” I continued, my voice as cold and hard as the riverstones at my feet. “You have two choices. Your first and best choice is to turn around, get in your shiny truck, and drive away.

You will forget you ever saw this dog and you will pray to whatever god you pretend to believe in that I forget what your faces look like. Your second choice is to try to take him from me. I let that hang in the air for a moment before adding, “But I feel it is my duty to inform you that I have had a very, very bad day. My patience is gone and I’ve already lost one arm. I’m not particularly attached to the other one if it’s in the service of beating some sense into a worthless coward like you.

” Caleb puffed out his chest, a last pathetic attempt to reclaim his shattered dominance. “You can’t just take our property. We paid good money for him.” “You forfeited your rights of ownership the moment you tied a rock to him and threw him in that river,” I said, my voice dropping to a near whisper, forcing them to lean in to hear me. “What you did today is called aggravated animal cruelty. in the state of Oregon. That’s a class C felony.

You’re looking at prison time. I have your faces memorized. I’m an excellent witness. I imagine the sheriff would be very interested in my testimony. So, you tell me. Do you want to add assault and battery to that charge sheet? Go ahead. Please give me a reason. They looked at each other.

The last of the bravado evaporated, leaving behind two scared, soft young men who had just learned a hard lesson about poking sleeping bears. They had seen a crippled old man and underestimated him. Now they saw something else in my eyes, something harder and older than they could possibly comprehend.

They saw a man who had been to the edge of the abyss and had walked back, and who was not afraid of them in the slightest. The taller one tugged on Caleb’s arm. Come on, man. Let’s just go. He’s crazy. The dog’s not worth it. Caleb hesitated, his petty pride waring with his instinct for self-preservation. He shot one last hateful glare at me. Whatever, old man. Keep the stupid mud. He’s probably broken anyway. They turned and crashed back through the woods, their movements clumsy and loud.

A minute later, I heard the sound of a powerful engine roaring to life, followed by the squeal of tires on the gravel access road as they sped away. And then there was silence. My quiet had returned, but it was a different kind of quiet now. It was fuller. It was shared.

I looked down at the little creature swaddled in my shirt. He had stopped shivering so violently. He looked up at me with dark, intelligent, almond-shaped eyes that held no malice, only a dawning, exhausted trust. He managed to lift his head and lick my chin. A tiny, tentative, grateful gesture. My own heart, a thing I’d long thought was mostly scar tissue and bad memories, felt like it cracked open just a little, letting in a warmth that had nothing to do with the sun. Okay, little guy. It’s okay.

Let’s go home. The walk back to my cabin was slow and deliberate. I was acutely aware of the precious, fragile weight in my arm. I could feel the faint, steady thump of his little heart against my own ribs. When we got inside, the warmth of the cabin was a blessing. I ran a warm bath in the deep utility sink, and as gently as I could, I worked the tangled, filthy net off his body.

I washed the river grime from his white fur, my one hand being as careful as I could. I towed him dry with the softest towel I owned, and then wrapped him in a thick, dry blanket, and set him on the hearth rug in front of the crackling wood stove.

He turned in three small circles, collapsed into the tightest possible ball, and fell into a deep, exhausted, twitching sleep. I made myself a mug of strong black coffee, my hand shaking as the last of the adrenaline finally burned away, leaving a profound bone deep weariness in its place. I sank into my old worn leather armchair, the one that perfectly molded to my body and just watched him.

For 10 years, this cabin had been my fortress of solitude. It had been a quiet, orderly, and empty place. Now, with the addition of this tiny, breathing, dreaming creature, it didn’t feel empty anymore. It felt like a home. He needed a name. Not just any name, a name that meant something. A name that honored the fighter he was.

I thought of the river, the cold, the unforgiving landscape. I thought of the great Kodiak bears of Alaska. Powerful, resilient, solitary survivors. Kota, I said aloud, the name feeling right on my tongue. The puppy’s ear twitched in his sleep, but he didn’t stir. Your name is Kota. He had been anchored to the bottom of a river, left for dead.

And in saving him, I realized with a startling clarity, he had just become an anchor for me. He was anchoring me here in the present, pulling me away from the ghosts of the past. He was a new mission, a new purpose, a new patrol. Those two men thought they were teaching him about being tough. They knew nothing.

Cota already knew more about being tough than they would in their entire pampered lives. He knew that when the world is trying to drown you, you fight. You kick and you struggle and you fight until you can’t fight anymore. And sometimes, if you are the luckiest soul in the world, someone shows up and fights for you. That evening, Cotto woke up.

He was shaky on his paws, but he followed me into the small kitchen. After a little coaxing, he ate a small bowl of scrambled eggs, his first real meal in my care. Afterwards, instead of returning to the hearth, he clumsily tried to climb into my armchair with me. I reached down and lifted him into my lap. He curled up against my chest, laid his head over my heart, and fell back asleep.

His little body radiating a surprising amount of heat, his soft breath, a steady, comforting rhythm. I sat there for hours, not moving, listening to him breathe. I looked out the window at the river, now a ribbon of silver and black under the moonlight. It had tried to take him. The world had tried to break him, but we had won.

We were two old soldiers, a one-armed man and a half-drowned pup, two survivors who had found each other on the battlefield of a quiet Tuesday morning. And I knew with a certainty that settled deep in the marrow of my bones that my life would never be quiet in the same way again. And for the first time in a very long time, I was profoundly, deeply, and humbly grateful.

This story is a testament to the fact that one person can make a difference. Animals like Kota are abandoned, abused, and thrown away every single day. And they don’t all have someone like Eli to be their hero. But you can be. You can be their voice.

By sharing this story, you shine a light on the cruelty they face and the compassion they deserve. Every subscription, every comment, and every share helps this message reach someone who needs to hear it. It tells the world that we will not stand by while the innocent suffer. Join our Pause and Us family. Be the voice for the voiceless.

Please take a moment to subscribe, share this story with your friends and family, and leave a comment below. If you believe in this cause, just type I love dogs to help this story be seen by more people. Your small act of kindness can create a wave of change. Thank you.